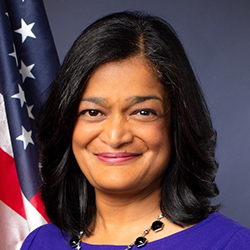

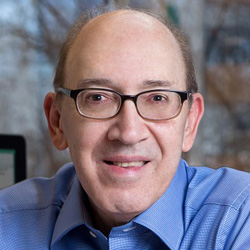

Charles Kamasaki

Senior Cabinet Advisor, UnidosUS | Fellow at Migration Policy Institute

The last time the federal government passed major immigration legislation was 1986, with a follow-up bill in 1990, and Charles Kamasaki was at the center of the action.

Now a senior cabinet advisor with UnidosUS, the country’s largest Hispanic civil rights advocacy organization (in the 1980s it was known as the National Council of La Raza), Kamasaki was an essential player in shaping the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA). His 2019 book, Immigration Reform: The Corpse That Will Not Die, details the history of the bill as well as the conditions that made its passage possible.

Signed into law by President Ronald Reagan, IRCA had three major features: It made it illegal for an employer to knowingly hire an undocumented worker, it gave legal status to the nearly three million immigrants who were in the country without documentation, and it strengthened border security.

Perhaps Kamasaki’s biggest contribution to today’s immigration debate is his ability to apply lessons from legislative efforts over nearly 40 years, particularly the passage of IRCA.

Notably, he sees a parallel between the years of failed immigration legislation leading up to the passage of IRCA in 1986 and the years of failed immigration legislation that have led to our current political landscape. In a 2019 speech talking about the failed immigration legislation of 2006, 2007, 2010, and 2013, he said, “It looks a lot like the dozen years or so that preceded IRCA’s passage.”

Kamasaki argues that in order for the country to pass more meaningful immigration legislation it will require concessions from key lawmakers and advocates on both sides.

He notes Republican Senator Alan Simpson’s willingness in 1986 to legalize over a million agricultural workers who were already in the country. Because of his stature with his colleagues, Simpson’s concession convinced others — including Reagan — to follow.

Kamasaki also recalls how, in the House, Rep. Esteban Torres led a faction of moderate Democrats to negotiate more progressive positions with his centrist colleague Rep. Romano Mazzoli.

Another lesson Kamasaki emphasizes is finding consensus that already exists. To that end, Kamasaki often points out that, across the political spectrum, there is widespread agreement that illegal border crossings are not good for the country. Among pro-immigration forces like Kamasaki, as well as pro-business conservatives, the prevailing view is that the economy functions better when everyone is brought out of the shadows. “Controlling the flow of migrants,” says Kamasaki, is the “reasonable, rational standard” that he incorporates into all of his policy and advocacy work.

SOURCES:

- Charles Kamasaki: Challenging Yourself The Bridgespan Group

- National Council of La Raza National Center for Public Policy Research — July 11, 2012

- Roots of La Raza National Review — May 31, 2010

- Thirty Years After the Immigration Reform and Control Act The Atlantic — May 23, 2016

- Book by UnidosUS Senior Cabinet Advisor Charles Kamasaki revisits last time immigration reform was successful UnidosUS Blog — October 1, 2019

- Charles Kamasaki Bio CHCI Leadership Conference 2019

- Will Immigration Reform Ever Succeed Again? The Legacy of IRCA & Its Enduring Lessons Migration Policy Institute — Video of Panel Discussion on Charles Kamasaki Book