IMMIGRATION NEWS BY THE NUMBERS – January 2023

February 2, 2023 – By Ariel Miller

77: Number of Democratic lawmakers who signed a letter condemning President Biden’s decision to expand Title 42 expulsions to cover Cuban, Nicaraguan, and Haitian migrants arriving at the border.

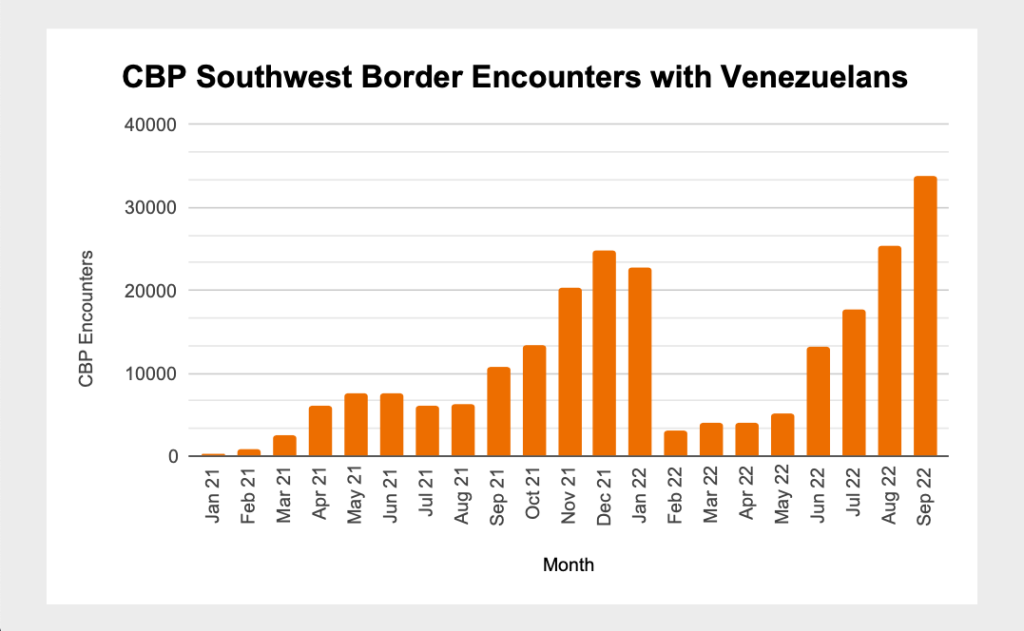

In the past month, the Biden administration announced that it would extend its rules developed for Venezuelan migrants in October of last year to include nationals of Cuba, Nicaragua, and Haiti. Under the new rule, nationals of these countries arriving at the border will be immediately expelled under Title 42 (the rule that expels individuals at the border, ostensibly as a public health measure), while those who remain in their home countries will have a chance to apply for humanitarian parole into the U.S. The change represents a massive expansion of both the Title 42 expulsion authority, which almost ended last month before a last-minute Supreme Court intervention, and the humanitarian parole program. Previously, the administration had pledged to accept a total of 24,000 Venezuelan migrants; now it plans to parole 30,000 migrants per month, or as many as 360,000 in the next year.

Although the expansion of the humanitarian parole program is significant, it represents only a fraction of the number of migrants showing up at the southern border. In December 2022, CBP reported 91,294 encounters with nationals of these four countries, primarily Cubans and Nicaraguans. The Biden administration’s new rule aims to disincentivize migrants from crossing the border to claim asylum, and preliminary numbers seem to show they’re achieving their goal. On January 25, the administration reported that the number of Haitians, Cubans, Venezuelans, and Nicaraguans apprehended at the border fell by 97 percent in the first weeks of January.

The move puts migrants who have already made the expensive and dangerous trip to the border in a difficult situation. Migrants can currently attempt to arrange an exemption from Title 42 in order to arrive at a port of entry and claim asylum, but appointments to do so can only be made through the government’s CBP One app. Users complain that appointments are few and far between, and that the app is glitchy, requires strong WiFi (which many migrants do not have), and is unavailable in languages other than English and Spanish, such as Haitian Creole. Furthermore, the criteria for an exemption from Title 42 are relatively narrow — migrants who attend an appointment but fail to meet these criteria are immediately expelled under Title 42 and barred from applying to the humanitarian parole program.

The new rule has been criticized from both the left and the right. A letter signed by 77 Democratic lawmakers blasted the “deeply inconsistent” expansion of Title 42, which the administration has previously sought to end. Additionally, while they expressed approval of the humanitarian parole program, they worried that it came at the expense of the longstanding right to claim asylum at the border, for which one needs no airfare, passport, or sponsor in the U.S — items that are mandatory for the parole program. Meanwhile, on January 24, 20 Republican state attorneys general filed a lawsuit attempting to block the humanitarian parole program, arguing that the Biden administration is significantly expanding immigration without the approval of Congress. In December, Sen. Chuck Grassley filed a bill attempting to curtail the administration’s ability to use humanitarian parole.

With prospects for passing any immigration legislation in the 118th Congress dim, the Biden administration has increasingly depended on whatever workarounds it can accomplish through executive authority. This month the administration also announced it would begin a pilot program allowing private citizens to sponsor refugees, and would expand the number of refugees the country accepts from Central America and the Caribbean. The administration is also developing a rule to bar individuals from applying for asylum if they passed through another country en route to the U.S. without seeking asylum there first — a controversial move that echoes the Trump administration’s policies.

$2 billion: Amount New York Mayor Eric Adams estimates the city will spend addressing the influx of migrant arrivals.

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott first began busing migrants from southern border towns to northern cities in April 2022, spawning copycat programs from former Arizona Gov. Doug Doucey as well as Democrats like El Paso Mayor Oscar Leeser, who tried to distance his city’s busing program from Abbott’s political message. Even secondary locations have joined in: after Denver Mayor Michael Hancock declared a state of emergency in mid-December due to an influx of migrants arriving from the border, Democratic Colorado Gov. Jared Polis announced on January 3 that he would send migrants who had been routed to his state onward to New York City and Chicago.

In response, New York City Mayor Eric Adams has begun advocating more vocally for the federal government to step in. In a news conference after Gov. Polis’s announcement, Mayor Adams called the federal government’s failure to manage migration a “national embarrassment,” and said New York has “no more room at the inn” for migrants. On January 14, he traveled to the southern U.S. border, a move common for federal lawmakers but unusual for a local leader. Ahead of that trip, he announced in a radio appearance that he expects the city will spend as much as $2 billion on migrants, although he did not specify the timeframe for this spending, and later said he hopes the federal government will cover the entire bill.

It’s true that New York has absorbed more migrants than any other destination. More than 40,000 migrants have arrived in New York in the last year, compared to roughly 5,150 migrants in Chicago and 8,700 migrants in Washington D.C. Yet adjusted for population, the story looks a little different. While New York has received one migrant for every 250 residents in the last year, Washington has received one for every 100, and the city of El Paso has served 19,329 migrants at its welcoming center since last summer — or one migrant for every 50 residents of the city. New York City’s budget for 2023 is 86 times larger than El Paso’s.

It’s hard to make an apples-to-apples comparison between different cities, whose needs and budgets vary so widely. But the unease about migration from city leadership across the country highlights how, in the absence of clear, efficient, and flexible federal policies that address the realities of modern migration, states and cities have been left scrambling to fill in the gaps.