IMMIGRATION NEWS BY THE NUMBERS – November 2022

December 1, 2022 – By Ariel Miller

$38.3 million: The amount the GOP spent on TV ads focusing on border security and immigration in the month leading up to the November midterms.

Across the country, Republicans sought to ride the Biden administration’s low approval ratings on border security and immigration to victory in the midterms, with mixed results.

The Republican strategy on immigration fared worst in Arizona, where Mark Kelly beat Blake Masters for a full term in the U.S. Senate and Katie Hobbs beat Kari Lake for the governorship. Kelly’s and Hobbs’s centrist immigration positions might have given them a boost with moderate voters. Hobbs has said the Biden administration isn’t “doing enough” to address the border, while Kelly has called the border a “mess.” Meanwhile, their opponents deployed the harshest of anti-immigration rhetoric. Masters has echoed “great replacement” rhetoric to argue that Democrats are trying to “import” immigrants to “change the demographics of this country,” while Lake said she would use Article 1, Section 10, of the U.S. Constitution to declare Arizona at war due to an “invasion” of border-crossers. A more fundamental shift on immigration in the state can be seen in the narrow passage of a ballot measure to offer in-state tuition to Dreamers, marking a dramatic shift from 16 years previously, when Arizonans voted by a wide margin to deny in-state tuition and other benefits to the state’s undocumented population. Some commentators have attributed the shift to grassroots organizing that began as a backlash against the last decade of strict anti-immigration measures in the state, such as the controversial passage of SB 1070 in 2010, which allowed local law enforcement to question and arrest individuals suspected of being undocumented, or the growing political influence of immigration hardliners like former Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio. Others point to Arizona’s changing demographics, with more left-leaning Californians having moved to the state.

Conversely, Republican candidates dominated in Florida, where Gov. Ron DeSantis won reelection by a wide margin. DeSantis grew his national profile on immigration by flying 50 migrants from San Antonio to Martha’s Vineyard in September. But despite the polarizing nature of what many called a political stunt, DeSantis won the Hispanic vote in Florida with a 15-point lead over opponent Charlie Crist. Just two years prior, Biden led Trump with Florida’s Hispanic voters by 7 points. Commentators point to DeSantis’s appeal to Latino voters as the key to him flipping several majority-Hispanic, historically left-leaning counties, including Miami-Dade. One explanation for DeSantis’s success with this demographic is his vocal condemnation of the socialist, communist, and leftist governments many Floridian Latinos emigrated from. However, DeSantis also won over the state’s blue-leaning Puerto Rican community, which has grown in recent years.

2.2 million: The number of times the Biden administration has expelled migrants under the Title 42 policy, which is set to end December 21 after a federal judge struck it down.

On November 15, a federal judge struck down the controversial pandemic-related Title 42 policy, arguing that the policy impaired the rights of migrants to claim asylum, upended standard procedure, and “does not rationally serve its stated purpose in view of the alternatives.” The Biden administration has until December 21 to end the policy.

The Biden administration has had an uneasy relationship with Title 42. Although the policy is explicitly designed to avoid the spread of viral disease in detention centers, all signs point to the policy being more of a Trump-era anti-immigration measure than a COVID-19 prevention policy. The CDC said the policy was no longer necessary over six months ago; in October, a key CDC health and immigration expert testified that he had never signed off on the original order, believing it to be a “misuse of a public health authority”; and in November 2021, the CDC’s former second highest official told Congress that “the bulk of the evidence at that time did not support this policy proposal.” Even if the policy were a necessary public health measure, in September Biden himself said the coronavirus pandemic was “over.”

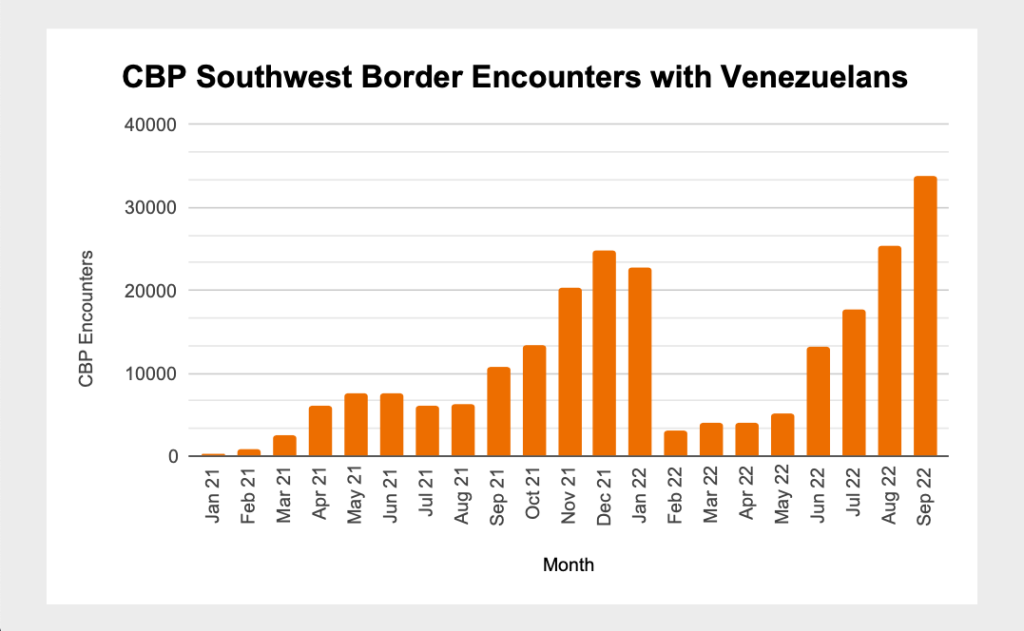

The Biden administration tried to roll back Title 42 itself once before; in May 2022, its efforts were blocked by an injunction. But the administration has also relied on the policy to manage an unprecedented level of migration at the southern border, using it to expel people 2.2 million times since 2021. Just last month, the administration expanded its immediate expulsion rights under Title 42 to apply to Venezuelans, who had previously been exempt from Title 42 deportations to Mexico, while simultaneously introducing a program that opened a narrow humanitarian window allowing paroled entry for vetted Venezuelans if they were matched with a U.S. sponsor. CBP encountered nearly 200,000 Venezuelans at the U.S. southern border in fiscal year 2022.

The push and pull on Title 42 highlights the conflicted relationship the Biden administration has had between trying to roll back Trump-era immigration policies and managing soaring levels of migration, all while coming under GOP fire for the border’s dysfunction. With comprehensive legislative reform still a distant dream, and with Biden’s executive policies on immigration often frozen in lengthy legal battles with Republican state attorneys general, the administration has been left with few other options as convenient and immediate as Title 42.

Speaking to Politico, U.S. immigration policy expert Doris Meissner said that the elimination of Title 42 will be a “major operational challenge.” At a November 17 briefing, Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas said that even with the end of Title 42, the DHS would continue looking for ways, including “enhanced expedited removal,” to limit the number of Venezuelan migrants.

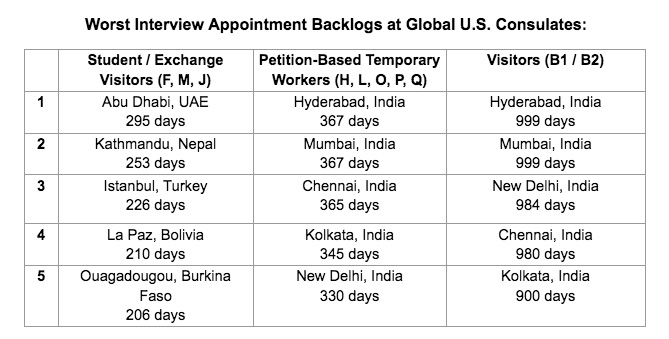

999: The number of days it takes to get an interview appointment for a U.S. tourist visa in Mumbai, India.

On November 17, the State Department held a briefing on its efforts to rebound from a global post-pandemic spike in visa processing wait times. To obtain a U.S. student, worker, or tourist visa, most applicants have to appear for an in-person interview at a U.S. consulate overseas. Due to staffing shortages, COVID-19 related consulate closures, and a backlog of people eager to return to international mobility after years of pandemic-related immigration restrictions, wait times to book these interviews soared.

In its briefing, the State Department outlined measures it has taken to reduce backlogs and pointed to their successes in the last year. Starting in December 2021, the State Department expanded its issuance of waivers that allow people who have traveled to the U.S. in the past to skip in-person interviews. Almost half of nonimmigrant visas in 2022 were issued without an interview. The State Department has also doubled consular hiring, and allowed officers in countries with lower demand to process visa applications from busier consulates remotely.

The State Department pointed to the success of these changes: the median wait time for a tourist visa interview fell from 192 days in July 2022 to about two months in November. However, the consulates in some countries have continued to struggle, with wait times growing.

India has been hit hardest by the backlogs. Under current conditions, Indian nationals must wait an average of about one year to get an appointment for an employment-based visa interview. For a tourist visa, the wait is even more stark. Based on State Department estimates, no consulate in India reports openings for tourist visa appointments for the next 900 days, minimum — approximately two and a half years. That’s up from an average of about 502 days in July 2022.

The backlogs have impacted individuals trying to come to the U.S. to work, as well as foreign workers already in the U.S. attempting to return home or host family for visits. The wait times have also frustrated U.S. businesses attempting to hire skilled guest workers.