IMMIGRATION NEWS BY THE NUMBERS – February 2023

March 1, 2023 – By Ariel Miller

71: Days until the Title 42 expulsion policy expires, triggering the Biden administration’s new asylum restrictions.

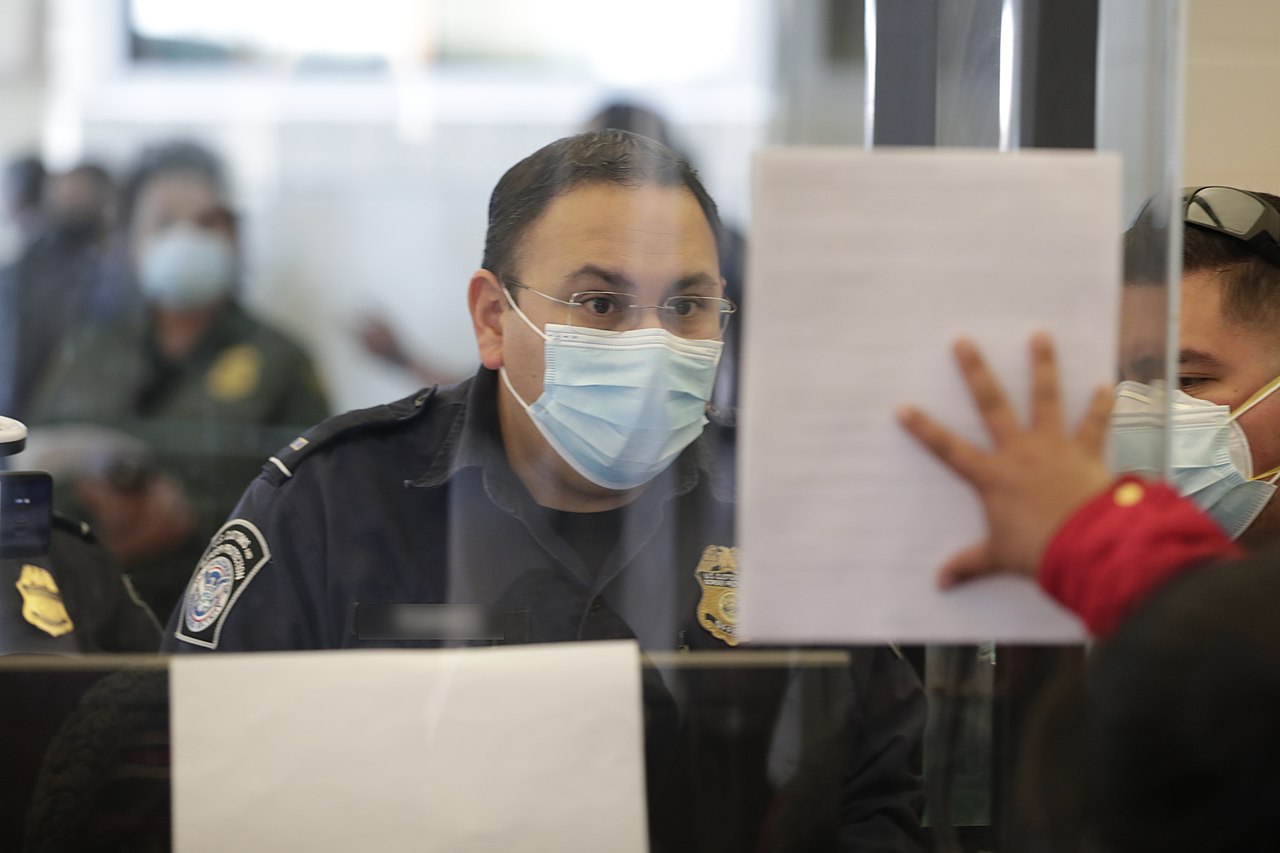

On February 21, the Biden administration unveiled a strict new policy proposal aimed at deterring asylum seekers from crossing the southwest border and surrendering to CBP between ports of entry. The move came as the administration announced it will formally end the COVID-19 public health emergency, which will cause Title 42, the long-lived pandemic-related expulsion policy, to expire on May 11 without further Supreme Court adjudication.

Under the new “rebuttable presumption” policy, individuals would be presumed ineligible to claim asylum if they present themselves to Border Patrol between ports of entry, and thus subjected to expedited removal. The new rule stipulates that, subject to exceptions, individuals will only be able to claim asylum if they schedule an appointment at a port of entry using CBP One, a mobile app that requires asylum seekers to fill out a form and submit certain biometric data.

There’s one catch: U.S. asylum law specifically states that asylum seekers do not have to present themselves at ports of entry. According to 8 U.S. Code § 1158, individuals may claim asylum upon their arrival in the U.S., “whether or not at a designated port of arrival.” However, the U.S. Code also says that an individual may be ineligible to claim asylum if they passed through a “safe third country” en route to the U.S. where the individual would not be threatened and would have access to a “full and fair [asylum] procedure,” without first attempting to claim asylum there. In order to give their new policy legal standing, the Biden administration is relying on selective enforcement of this “safe third country” clause: show up between ports of entry, and they will enforce it; schedule an appointment at a port of entry, and they will not.

It is likely that the legality of this interpretation will be significantly challenged. Previously, the Trump administration also sought to use the “safe third country” clause to restrict asylum more broadly, announcing a policy that would completely bar any asylum seeker if they passed through a safe third country en route to the U.S. without first seeking asylum there. The policy was first blocked on procedural grounds and later struck down by a federal appeals court that ruled the administration had not done enough to prove that other countries like Mexico and Guatemala were in fact safe places to claim asylum for people fleeing neighboring Central American countries. Several advocacy groups have already threatened to sue the Biden administration.

Individuals can be exempted from the new policy if they are able to show that they were unable to use the CBP One app due to “a language barrier, illiteracy, significant technical failure, or other ongoing and serious obstacle” (the app is not available in languages other than Spanish and English, and has faced criticism for being glitchy). Other exemptions will be made for people experiencing acute medical emergencies or immediate threats to their life or safety, such as the “imminent threat of rape, kidnapping, torture or murder.” The policy does not apply to unaccompanied minors.

271,000: Number of Ukrainians the U.S. has received since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

February 24 marked the one-year anniversary of the Russia-Ukraine War. In the past year, more than 8 million Ukrainians have fled for neighboring countries, and another 5.9 million Ukrainians remain internally displaced.

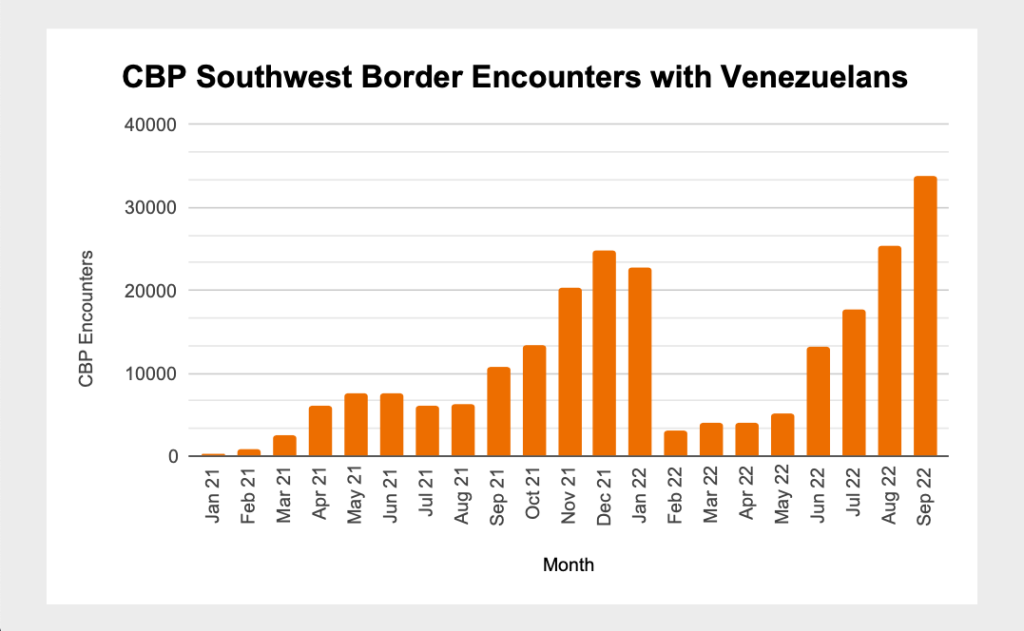

While President Biden initially set a goal to receive 100,000 Ukrainians, the U.S. has far surpassed that goal, accepting more than 271,000 Ukrainians in the last year. Although these individuals are often referred to as “refugees” in a colloquial sense, only a fraction have arrived through the traditional refugee system. Instead, 117,000 have arrived through the administration’s Uniting for Ukraine program, which connects Ukrainians seeking shelter with private U.S. sponsors and provides them with temporary “humanitarian parole”— the same temporary protection the administration has used in its programs for Afghans, Venezuelans, Cubans, Nicaraguans, and Haitians. Additionally, many Ukrainians have flown to Mexico (and a far smaller number have flown to Canada) to claim asylum at U.S. borders. Between February 2022 and January 2023, U.S. CBP reported 141,853 encounters with Ukrainian nationals at U.S. borders.

The traditional refugee settlement system has struggled to bounce back after slashes during the Trump administration, when historically low refugee admissions led many resettlement agencies to shutter or reduce operations. In fiscal year 2022, which ended in September, the U.S. admitted only 25,465 refugees despite setting the refugee cap at 125,000. Last month, the government unveiled a pilot program that would replicate the private sponsorship model first developed in the administration’s temporary humanitarian parole programs, allowing U.S. citizens to take on the role traditionally filled by non-profit refugee resettlement agencies.

“A Couple Thousand”: An estimate of “Documented Dreamers” who stand to benefit from a new USCIS policy aimed at preventing dependents of temporary immigrants from aging out of legal status in the final months of their adjudication process.

On February 14, USCIS released a new policy aimed at preventing the children of temporary legal immigrants from aging out of legal status in the final stretch of the process of adjudicating their permanent status applications. The policy will also allow some applicants who previously aged out to contest the decisions on their applications.

When the child of an immigrant with temporary status in the U.S. turns 21, they are no longer covered (no longer “documented”) under their parent’s legal status or permanent residency application. Although pathways exist for these dependents to adjust their status before they age out, severe backlogs have meant that many dependents wait for years to be processed and age out before their applications are adjudicated. These young adults, who grew up in the United States, must then either apply for a visa as a foreign student or worker, or self-deport to their countries of origin. Ideaspace has previously reported on these “Documented Dreamers” in Congressional Note No. 4.

The new policy is a narrow change to when USCIS will “freeze” the age of applicants. Every month, USCIS releases a bulletin with two charts of dates related to pending applications: the first acts as a “heads up,” letting applicants know that USCIS believes it will be able to consider their applications soon and they may begin filing their paperwork, and a second “final action date” chart which lists the actual applications USCIS is currently able to adjudicate. Previously, some dependent applicants would file their paperwork only to age out in the interim between the “heads up” and the “final action date,” a gap that could be anywhere from several months to several years. The new policy will instead freeze applicants’ age based on the first chart, closing the gap and eliminating uncertainty.

The policy change doesn’t address the lengthy wait times that cause young people to age out of protection in the first place. In a bulletin, USCIS cautioned that the change “will not prevent all children from aging out before an immigrant visa is available to them, nor will it prevent children from losing nonimmigrant status derived from their parents upon reaching the actual age of 21.” USCIS could not report how many people would be affected by the change, but in conversation with Ideaspace, Dip Patel, founder of the advocacy organization Improve the Dream, estimated that the change might benefit “a couple thousand” Documented Dreamers, including those who will now be able to contest previous denials.

“We’re very grateful for the change, but really, this one thing from USCIS is no reason to give them a lot of credit for doing much to help this population,” said Patel. “They can and should do a lot more to protect this population. There’s a lot of actual regulatory changes they can make, and sub-regulatory changes as well, but this is the lowest of the lowest hanging fruits.”