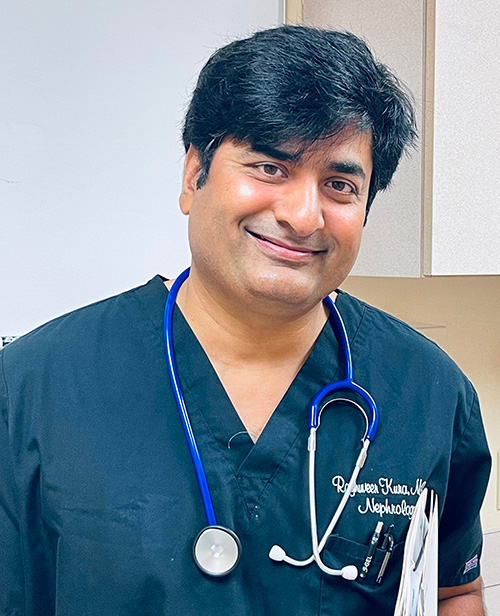

In accordance with the requirements of his J-1 educational exchange visa, Dr. Raghuveer Kura was expected to return to his home country of India upon completion of his nephrology training at the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pennsylvania. Only after two years back in his home country could he then apply for an immigrant visa that would allow him to properly launch a medical career in the United States. Instead, Dr. Kura applied for a Conrad 30 Waiver, a little known federal program that would allow him to stay in the U.S. while pursuing a green card in exchange for bringing his talents to an underserved area in dire need of more doctors. Dr. Kura was granted the Conrad 30 waiver and was allowed to begin practice in Poplar Bluff, Missouri.

“When I first came to Poplar Bluff — it was back in 2010 — I never thought I’d be staying here for more than three years,” said Dr. Kura, explaining that once he got his green card, the plan was to decamp for a major city, or at least to someplace bigger than this rural Missouri town of less than 17,000 people. He assumed he would want to leave Poplar Bluff for a more populous place that would more closely fit the vision of the American dream he had as a teenager back in India.

“But not long after arriving here, I start learning stories of patients who need to drive for hours to get dialysis, and I’m the only nephrologist in the region,” said Dr. Kura, who treats patients for kidney failure, hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease. “I stayed and started a dialysis unit in 2015 with 15 to 20 patients. I now have 90 patients and the volume is increasing.”

Despite his commitment and best efforts to serve his part of Missouri, Dr. Kura said, “We need more nephrologists. … These immigration restrictions inevitably impact patients with life-and-death consequences.”

In addition to relaying his story to Ideaspace, Dr. Kura shared his experience with the House Subcommittee on Immigration and Citizenship earlier this year, where lawmakers are considering advancing in Congress the Conrad State 30 and Physician Access Reauthorization Act.

In addition to relaying his story to Ideaspace, Dr. Kura shared his experience with the House Subcommittee on Immigration and Citizenship earlier this year, where lawmakers are considering advancing in Congress the Conrad State 30 and Physician Access Reauthorization Act.

The Conrad 30 Waiver program was first created as the “Conrad 20” in 1994 by its namesake, U.S. Sen. Kent Conrad of North Dakota, as a way to fill doctor shortages in his rural state and other medically underserved areas across the country. In its original form, the program gave each state 20 waivers annually. In 2003, Congress reauthorized the program and increased the number of state-sponsored waivers to 30 per year. But in recent years, the program’s status has grown precarious; it has survived through temporary, one-year funding package extensions. The Conrad State 30 and Physician Access Reauthorization Act would formally reauthorize the program for three years, increase the number of waivers to 35 annually, and provide for further adjustments depending on demand.

Thus far, the bill has garnered an astonishing amount of bipartisan support in an era marked by intense polarization in Congress — especially on matters of immigration. The House bill has 75 Democratic cosponsors and 35 Republican cosponsors, while a companion bill in the Senate, introduced by Democratic Sen. Amy Klobuchar, boasts 25 cosponsors, the majority of which come from the GOP.

Thus far, the bill has garnered an astonishing amount of bipartisan support in an era marked by intense polarization in Congress — especially on matters of immigration. The House bill has 75 Democratic cosponsors and 35 Republican cosponsors, while a companion bill in the Senate, introduced by Democratic Sen. Amy Klobuchar, boasts 25 cosponsors, the majority of which come from the GOP.

“I think the success the bill has had on that front is really a reflection of the approach of the bill, which is to use immigration to solve issues that we’re having domestically,” said a Democratic source who has worked on the legislation, who wished to remain anonymous.

The bill’s bipartisan prospects are helped by its narrow focus on domestic healthcare needs. Also, the fact that most U.S. “healthcare deserts” are in rural districts, which are overwhelmingly represented by Republicans, helps build GOP interest in the Conrad 30 Waiver program.

“I think that’s part of the reason why so many Republicans are on board, because I think this is a real need for people in rural areas,” said the Democratic source. “Senator Thune is on the bill, who represents South Dakota. I think the fact that he’s on the bill is really a reflection that this is something that people in South Dakota really feel.”

“I think that’s part of the reason why so many Republicans are on board, because I think this is a real need for people in rural areas,” said the Democratic source. “Senator Thune is on the bill, who represents South Dakota. I think the fact that he’s on the bill is really a reflection that this is something that people in South Dakota really feel.”

Nevertheless, Republican members of Congress who spoke at the House Subcommittee hearing in February were unanimous in their opposition to using immigration to address the U.S. doctor shortage. Among other concerns, they cite lifting the vaccine mandate for U.S. doctors and tapping into the pool of American medical school graduates who have failed to match with residency programs as preferable ways to address the problem.

“We’ve refused to match [to residency programs] over 10,000 Americans who have their medical degrees, we fired 10,000 healthcare workers because, in their professional medical judgment, they should not be receiving the vaccine — that’s 20,000 right there,” said Rep. Tom McClintock, Republican of California and ranking member of the House Subcommittee on Immigration and Citizenship. “Yet we’re told the answer is, ‘Import more foreign nationals.’”

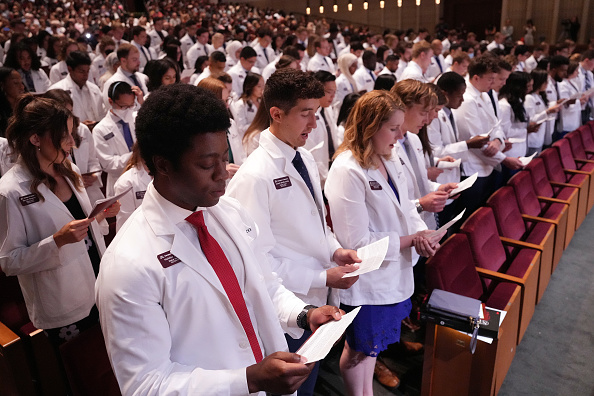

On the matter of American doctors failing to match with residency programs, David Skorton, president of the Association of American Medical Colleges, assured the House subcommittee that the criteria for matching was purely objective, and that no preferential treatment is given to foreign nationals. The Democratic source put it more bluntly in discussing the foreign nationals who are seeking residencies: “These people are more qualified than the doctors they’re referencing [who have had difficulty finding residencies].”

On the matter of American doctors failing to match with residency programs, David Skorton, president of the Association of American Medical Colleges, assured the House subcommittee that the criteria for matching was purely objective, and that no preferential treatment is given to foreign nationals. The Democratic source put it more bluntly in discussing the foreign nationals who are seeking residencies: “These people are more qualified than the doctors they’re referencing [who have had difficulty finding residencies].”

Furthermore, the source added, “The fact that the bill has been so successful in getting support from Senate Judiciary Committee Republicans like John Cornyn and Thom Tillis is a reflection that when you really dig into the numbers, this is a solution that people who care about rural healthcare can get behind.”

Those numbers about the healthcare system as a whole show a projected shortage of 124,000 doctors by 2034, according to a report by the Association of American Medical Colleges. This isn’t just a future concern. More than 86 million Americans live in areas that already have an insufficient number of primary care physicians, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Immigrant doctors would by no means cover the growing demand, but they would help close the gap. Studies show that many communities in the U.S. are already heavily reliant on foreign doctors. According to the American Medical Association, nearly 21 million people live in areas of the U.S. where foreign-trained physicians account for at least half of all physicians.

A 2016 report by the Rural Health Research Center at the University of Washington found that states were collectively recruiting up to 1,000 immigrant physicians annually through the Conrad 30 Waiver program to practice in underserved communities. According to a 2021 survey by Irvine Legal, a law firm that advises healthcare professionals on immigration matters, 23 states were using their full allotment of Conrad waivers, including Republican-led governments like Arkansas, Idaho, South Carolina, Texas, and West Virginia. Not far behind were deeply rural states like Mississippi, South Dakota, and Utah using 20 or more of their annual allotment.

A 2016 report by the Rural Health Research Center at the University of Washington found that states were collectively recruiting up to 1,000 immigrant physicians annually through the Conrad 30 Waiver program to practice in underserved communities. According to a 2021 survey by Irvine Legal, a law firm that advises healthcare professionals on immigration matters, 23 states were using their full allotment of Conrad waivers, including Republican-led governments like Arkansas, Idaho, South Carolina, Texas, and West Virginia. Not far behind were deeply rural states like Mississippi, South Dakota, and Utah using 20 or more of their annual allotment.

The Conrad 30 Waiver program benefit often endures beyond the commitment period. The 2016 Rural Health Research Center report found that 55 to 80 percent of waivered physicians intended to remain in their communities upon completion of the three-year term of service. With this new bill expanding the service obligation to five years, the retention rate of waivered physicians in medically underserved communities is likely to rise.

Dr. Kura is proof positive of how the Conrad 30 Waiver program can have long-lasting benefits for places like Poplar Bluff. “I consider this my home now,” he told the House subcommittee. “I have established my roots. I have established relationships with my patients…. My patients know my children.”

In addition to his commitment to staying in Poplar Bluff, Dr. Kura exhibits the entrepreneurial spirit so often found in immigrants. “I want to grow this place, I want to help people here,” he said of his wish to expand his practice throughout rural Missouri. “But unfortunately, I’m not able to get help. We need some kind of legislative act in order to get more [doctors to rural Missouri].”

In addition to his commitment to staying in Poplar Bluff, Dr. Kura exhibits the entrepreneurial spirit so often found in immigrants. “I want to grow this place, I want to help people here,” he said of his wish to expand his practice throughout rural Missouri. “But unfortunately, I’m not able to get help. We need some kind of legislative act in order to get more [doctors to rural Missouri].”

Sen. Klobuchar hopes that the Conrad State 30 and Physician Access Reauthorization Act can answer Dr. Kura’s call. Failure to retain these talented graduates of U.S. medical schools, she said earlier this year in a hearing held by the Senate Judiciary Subcommittee on Immigration, Citizenship, and Border Safety, represents a “self-inflicted economic wound.”

As Ideaspace found in its reporting on the Temporary Family Visitation Act, since last year’s failure in Congress to pass broad-based reform of the immigration system (such as a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants), there’s an opening now for Democratic leadership to press for more modest improvements like the Conrad State 30 and Physician Access Reauthorization Act. With 13 Republican senators already signed on as cosponsors, that’s more than enough bipartisan support to get past the 60-vote filibuster threshold.

Read More:

Congressional Note No. 2

Capitol Hill Briefing No. 7