When migrants present themselves to a Border Patrol agent or customs officer and make an asylum claim, U.S. policy is to hold them in detention while that claim is adjudicated. There are opportunities for some individuals to be paroled and reside in the U.S. until their case is concluded, but every asylum seeker will start the asylum adjudication process from a holding cell without being charged with a crime.

This policy is relatively recent, tracing back to the last days of the Carter administration when large numbers of Haitians who were fleeing an autocratic rule started showing up at U.S. ports of entry, many seeking asylum. The administration resorted to using spaces immediately available to the federal government, which included military bases and federal penitentiaries.

This ad hoc response was formalized as policy during the early days of the Reagan administration, when large numbers of Cubans began arriving with asylum claims, and U.S. Attorney General William French Smith began citing what would become the prevailing rationale for detaining immigrants: It was necessary as a deterrent to future migrants who might consider coming to the U.S.

But in the decades since, U.S. courts have consistently confirmed that deterrence is not a legally acceptable reason for immigrant detention. As recently as 2015, the federal district court in Washington D.C. concluded that, given the civil nature of the proceedings, detention as a deterrent tool for future migrants was a violation of the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process clause. As a result, the rationale for immigrant detention has shifted to a focus on guarding against asylum seekers skipping out on court appearances.

But in the decades since, U.S. courts have consistently confirmed that deterrence is not a legally acceptable reason for immigrant detention. As recently as 2015, the federal district court in Washington D.C. concluded that, given the civil nature of the proceedings, detention as a deterrent tool for future migrants was a violation of the Fifth Amendment’s Due Process clause. As a result, the rationale for immigrant detention has shifted to a focus on guarding against asylum seekers skipping out on court appearances.

“The law allows detention for the sake of just keeping tabs on where an individual is,” says García Hernandez, a professor at Ohio State University and the author of Migrating to Prison: America’s Obsession with Locking Up Immigrants. “For the sake of making sure that they show up to the hearings, for the sake of keeping the community safe, but not for the sake of sending a message to other people that they shouldn’t come.”

Given this legal reality, a central question emerges: Is detention the most effective and cost-efficient approach to ensuring court compliance?

***

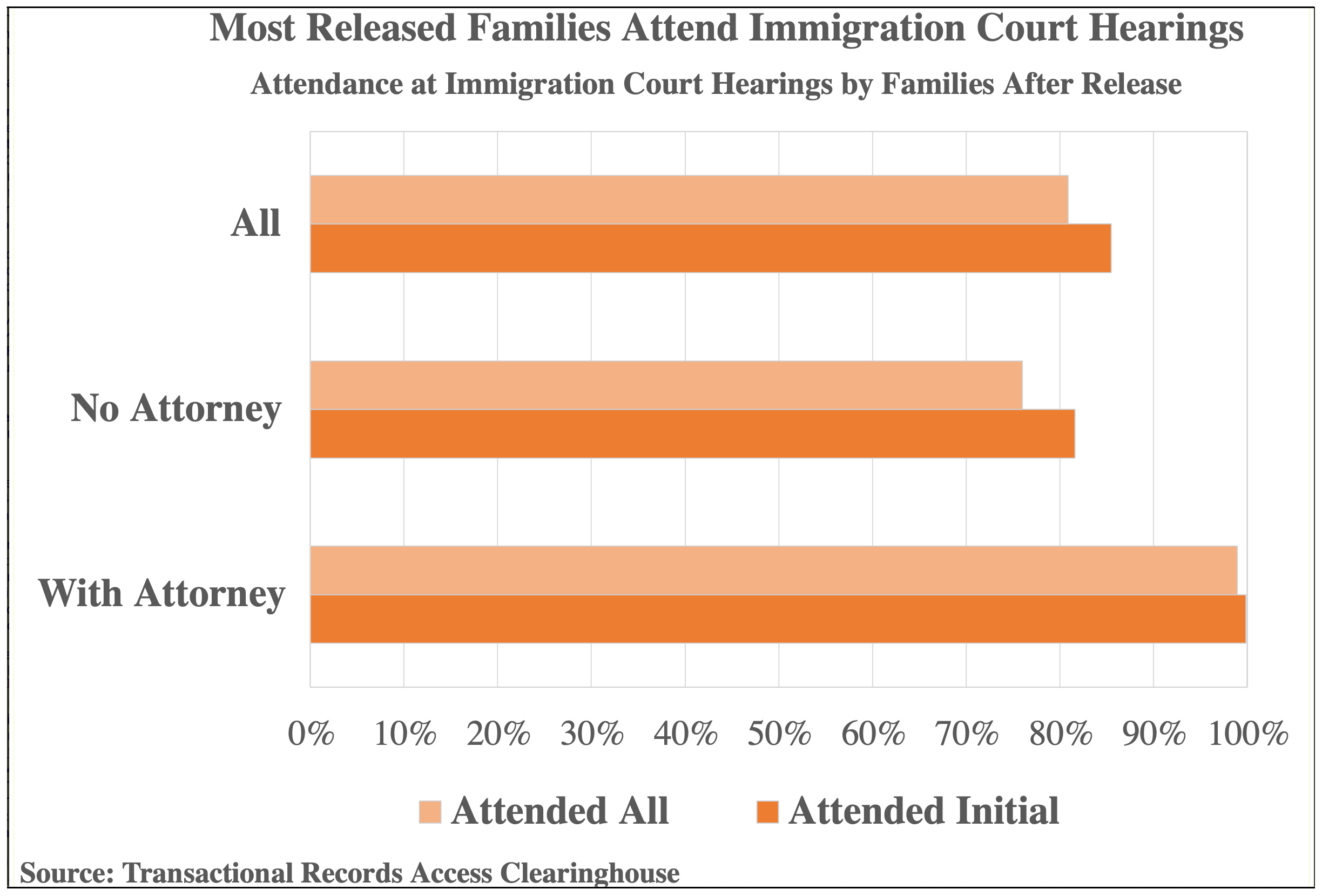

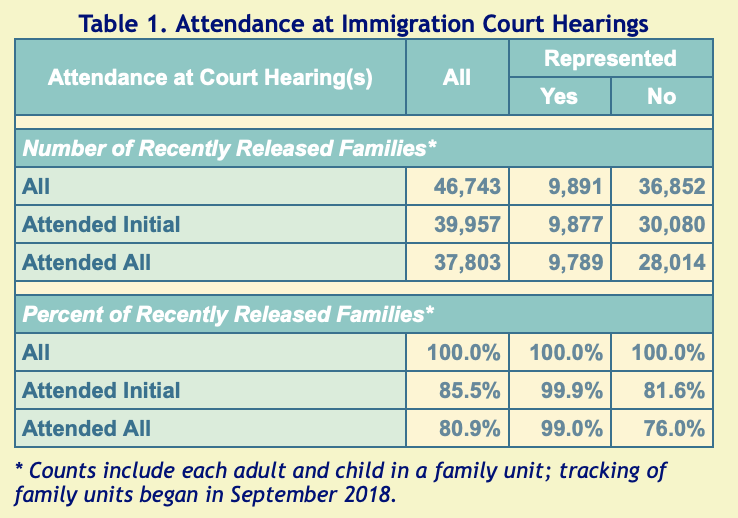

Statistically speaking, the most reliable indicator for court compliance is access to counsel. Austin Kocher, an assistant research professor at Syracuse University, works with the school’s Transactional Research Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), which keeps a database of immigration-related statistics. Over time, Kocher and his colleagues have assembled multiple cohorts, each with approximately 50,000 asylum seekers, to analyze and track their experience through the adjudication process. “The last time we did that,” says Kocher, referring to a May 2019 report, “we found that for those people who had an immigration attorney, more than 99 percent attended all of their hearings. Basically the answer is if people have an attorney, they go through the whole process, they show up to all the hearings, and they typically accept the outcome.”

Similarly, a 2014 study conducted by the Government Accountability Office showed that of the immigrants who were put into detention-alternative programs, many with case management services, 95 percent completed their court proceedings.

“From a human rights perspective,” says Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, Policy Director at American Immigration Council, a nonprofit organization that advocates on behalf of immigrants, “when we have other options, like alternative-to-detention programs, ensuring that people know how to get to court, case management opportunity, case management programs, things that basically help people navigate a complicated system, we can see that detention isn’t necessary. There might be some arguments in some rare circumstances, say, terrorists, or people who are murderers, or others with serious criminal records where the government might say, ‘Well, we have some sort of public safety rationale for it,’ but that’s certainly not what detention is being used primarily for today.”

“From a human rights perspective,” says Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, Policy Director at American Immigration Council, a nonprofit organization that advocates on behalf of immigrants, “when we have other options, like alternative-to-detention programs, ensuring that people know how to get to court, case management opportunity, case management programs, things that basically help people navigate a complicated system, we can see that detention isn’t necessary. There might be some arguments in some rare circumstances, say, terrorists, or people who are murderers, or others with serious criminal records where the government might say, ‘Well, we have some sort of public safety rationale for it,’ but that’s certainly not what detention is being used primarily for today.”

What’s more, as asylum seekers are not charged with a crime, they are not guaranteed access to counsel under the Sixth Amendment of the Constitution. Lacking such assured access, 70 percent of all those in immigration detention — not just asylum seekers — navigate the complexities of the court system without a lawyer.

In an April 2021 report outlining how federally-funded universal access to immigration counsel might be realized, authors at the Vera Institute wrote that “it is incumbent on the federal government to bear the expense of representation for immigrants to safeguard their basic due process rights, just as it does in the criminal public defender system.”

The report notes that roughly 60 state, county, and municipal programs are already offering universal access to counsel for immigration court cases; it outlined what’s required to successfully start a program, best practices over time, and funding models in the absence of federal money. “As programs grow,” the authors wrote, “they can achieve greater efficiencies of scale. Many programs start with modest initial investments commensurate with the local jurisdiction’s size and budget.”

The report notes that roughly 60 state, county, and municipal programs are already offering universal access to counsel for immigration court cases; it outlined what’s required to successfully start a program, best practices over time, and funding models in the absence of federal money. “As programs grow,” the authors wrote, “they can achieve greater efficiencies of scale. Many programs start with modest initial investments commensurate with the local jurisdiction’s size and budget.”

Smaller cities, according to the report, can start a universal immigration counsel program with a budget of $200,000 to $500,000, whereas a larger city such as Chicago started its program with $1.3 million. “Initial investments,” the report states, “should be planned to increase incrementally over time to support a fully-funded infrastructure for representing everyone in the jurisdiction who is in need. This would allow legal teams to build out capacity at a manageable pace.” Two representative examples of such increases are Prince George’s County, which amended its budget from $100,000 to $500,000, and New Jersey, which amended funding from $3.1 million to $6.2 million.

It’s important to note that these budgets represent programs applied to all immigration court cases in the given jurisdiction; universal counsel for asylum seekers only — as a starting point — could be realized for far less funding, as asylum seekers make up just 45 percent of pending immigration court cases.

The Vera Institute report states that “local and state programs are important stepping-stones for making [universal counsel] a reality, by helping develop the necessary infrastructure for removal defense, demonstrating the impact of legal representation, and building power in communities for this national movement.”

The budgets for these universal counsel programs are dwarfed by the ongoing costs of detention. In 2022 alone, the federal budget for immigration detention is $2.9 billion. Given the relatively low cost of existing universal counsel programs in populous states like New Jersey, Texas, and New York, a federally-funded program would likely save the government money if it replaced mass detention.

The budgets for these universal counsel programs are dwarfed by the ongoing costs of detention. In 2022 alone, the federal budget for immigration detention is $2.9 billion. Given the relatively low cost of existing universal counsel programs in populous states like New Jersey, Texas, and New York, a federally-funded program would likely save the government money if it replaced mass detention.

Beyond the savings, there are the moral issues, originally raised by the Eisenhower administration. In 1954, U.S. Attorney General Hebert Brownell stood in the middle of Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field and, surrounded by tens of thousands of individuals who were participating in a naturalization ceremony, announced that the federal government was closing Ellis Island and would end the practice of routinely holding arriving immigrants in detention. It was a decision driven by a moral imperative and Cold War dynamics — and one that lasted until the end of the 1970s.

“The Soviet Union had a pretty strong card to play,” says García Hernandez. “The Soviets say to other countries, ‘Look, whatever the United States is telling you, they don’t like you. The best evidence of that is the fact that the moment your citizens get to New York, they lock them up. They stick them behind barbed wire. That’s not the way you treat friends. That’s not the way you treat allies.’”

The moral considerations of immigration detention have only grown more acute with as many as 51,000 immigrants detained at a time, as was the case in early 2020. Sexual assault, abuse, and deaths are well documented within the U.S. immigrant detention complex, both in private and government-run facilities. In 2020, there were more deaths in immigration detention centers than in any previous year. And one could argue now, just as Attorney General Brownell did in 1954, that America’s moral standing on this issue remains an important geopolitical consideration when it comes to U.S. foreign policy toward such hostile states as Russia and China.

For those who advocate against detention, the moral imperatives have always been apparent but the opportunity to change policy budgetarily has only recently gained momentum.

“We do a lot of work in the appropriations area,” says Setareh Ghandehari, Advocacy Director at Detention Watch Network, an immigration detention watchdog. “So we’re really working toward cutting ICE and CBP funding through the appropriations process. And of course one of the focuses there being cutting detention funding. We recently relaunched our transformative budget, which talks a little bit about where we want to see investments.” That vision, ultimately, includes guaranteed legal counsel for anyone facing immigration court.

“We do a lot of work in the appropriations area,” says Setareh Ghandehari, Advocacy Director at Detention Watch Network, an immigration detention watchdog. “So we’re really working toward cutting ICE and CBP funding through the appropriations process. And of course one of the focuses there being cutting detention funding. We recently relaunched our transformative budget, which talks a little bit about where we want to see investments.” That vision, ultimately, includes guaranteed legal counsel for anyone facing immigration court.

“If we give people the freedom and the resources that they need,” says Ghandehari, “we’ll see what a just system can look like that doesn’t include caging people.”

In addition to the Vera Institute, the Center for Popular Democracy and the National Immigration Law Center have also advocated for federally-funded universal access to immigration counsel. And in a survey conducted by the Vera Institute, 67 percent of Americans support the idea of universal counsel.

Imagining a shift away from detention writ large toward federally-funded universal counsel for immigration cases is, at first glance, politically untenable, particularly when considering the lobbying power of public corrections unions and the private prison industry.

“We fetishize prisons,” says García Hernandez, “and we are perfectly willing to imprison just about anyone. No one can curry political favor by saying, ‘Oh, actually we shut down that prison.’ These facilities employ people and they’re located in places where it’s hard to get decent paying jobs. It’s hard for any elected official, especially in poor rural parts of the United States where these facilities tend to be located, to say, ‘Well, we’ll shut down that facility and those 200 people, they’re just going to be out of a job.’”

If job loss concerns at detention facilities are effectively addressed, a federal move toward universal counsel for immigration cases could achieve surprisingly broad political appeal. The list of potential benefits is long. A universal counsel policy could drastically reduce the need for detention, all but ensure court appearances, save money and save lives.

Read More:

Strategic Inquiry No. 8