With the 118th Congress now convened, lawmakers and advocacy groups are recalibrating their expectations for what can be achieved on immigration in the U.S. House of Representatives, which, for the first time in four years, is controlled by the Republican Party. Newly installed Republican House Speaker Kevin McCarthy has vowed to prioritize border security, and with MAGA stalwart Jim Jordan now the chair of the House Judiciary Committee (which oversees the all-important House Subcommittee on Immigration, Citizenship, and Border Safety), many seasoned observers warn that any congressional action on the 11 million undocumented immigrants currently residing in the United States will almost certainly have to wait until more favorable conditions present themselves in the House.

Maunica Sthanki, who served as Democratic counsel for the House Judiciary Committee from 2014 to 2018, believes the prospects for any movement on immigration in the lower chamber are bleak.

“In the next two years, with Republicans in control of the House, particularly with the nature of the House Republican caucus — many of whom have sort of extreme right-wing views — I don’t believe that even a small provision can pass,” Sthanki said at a December panel discussion held by the American Bar Association’s Commission on Immigration.

“In the next two years, with Republicans in control of the House, particularly with the nature of the House Republican caucus — many of whom have sort of extreme right-wing views — I don’t believe that even a small provision can pass,” Sthanki said at a December panel discussion held by the American Bar Association’s Commission on Immigration.

Casey Higgins, Sthanki’s Republican counterpart in the same panel discussion, who served as a senior policy advisor to House Speaker Paul Ryan, agreed that any movement on comprehensive immigration reform is politically impossible in the 118th Congress. But she did point to one way in which the narrowly divided House could and should operate.

“[With comprehensive immigration reform] every member has a reason to vote no instead of every member having a reason to vote yes, and it has collapsed under its own weight,” said Higgins, adding that this is more true than ever in the 118th Congress. “Instead, take steps in the right direction to do confidence building measures that show that we are not completely inept, that we can do this without the political ramifications burning the place down. We can build the confidence to do more, and more, and more.”

By “confidence building measures,” Higgins was talking about narrow pieces of legislation that would reform the immigration system piecemeal. Often the biggest obstacle in Congress to gaining support for such discrete measures is the notion that a lawmaker only has so much political capital to spend. As the thinking goes, if you spend it on something small, like the Temporary Family Visitation Act (which would create a temporary visa for foreign nationals who wish to visit family members in the U.S.), you wouldn’t have any capital left over for bigger priorities like the DREAM Act.

By “confidence building measures,” Higgins was talking about narrow pieces of legislation that would reform the immigration system piecemeal. Often the biggest obstacle in Congress to gaining support for such discrete measures is the notion that a lawmaker only has so much political capital to spend. As the thinking goes, if you spend it on something small, like the Temporary Family Visitation Act (which would create a temporary visa for foreign nationals who wish to visit family members in the U.S.), you wouldn’t have any capital left over for bigger priorities like the DREAM Act.

“I’ve heard that a lot, ‘Don’t go for anything small, because we’re going for a big immigration reform,’” Rep. Scott Peters, a Democrat whose California congressional district borders on Mexico, told Ideaspace. “I’m now much more open to helping farmers directly if we can get a bill passed, because I think it’s been pretty clear over the last 10 years, or, I don’t know, since 1986 (when Pres. Ronald Reagan signed the Immigration Reform and Control Act, the last major overhaul to the U.S. immigration system), that comprehensive immigration reform is maybe an elephant that has to be eaten one bite at a time.”

Rep. Peters hopes that smaller immigration bills like the Temporary Family Visitation Act (which he introduced in the House in May of 2021) and the Farm Workforce Modernization Act (which would provide a path to legalization for millions of undocumented agricultural workers) can find more purchase in a House where comprehensive immigration reform is effectively off the table.

“So for me,” said Rep. Peters of the immigration landscape in the 118th Congress, “I’m willing to take smaller bites.”

Beyond concentrated efforts to pass more modest immigration proposals with bipartisan support, Rep. Peters believes that House Democrats should spend the next two years reframing the immigration debate on economic grounds.

“It’s been my experience that there’s a lot of conceptual agreement in Congress about what needs to happen with immigration around the effects on the economy and employment,” said the congressman. “I think that Democrats have to go on the offensive. Immigration has become a really important response to inflation, our labor shortages, and economic growth. Republicans used to be for those things, and we should make sure that people understand that they’re not. I think we need to call them out. We have, what, almost 600,000 DACA holders in the United States, and are we going to deport them? I mean, there’s a worker shortage that’ll only be exacerbated if we don’t protect DACA. It would be disastrous for the economy. We need to explain it in those terms.”

“It’s been my experience that there’s a lot of conceptual agreement in Congress about what needs to happen with immigration around the effects on the economy and employment,” said the congressman. “I think that Democrats have to go on the offensive. Immigration has become a really important response to inflation, our labor shortages, and economic growth. Republicans used to be for those things, and we should make sure that people understand that they’re not. I think we need to call them out. We have, what, almost 600,000 DACA holders in the United States, and are we going to deport them? I mean, there’s a worker shortage that’ll only be exacerbated if we don’t protect DACA. It would be disastrous for the economy. We need to explain it in those terms.”

Casey Higgins, the Republican operative who worked for Paul Ryan, agrees, at least when it comes to reframing the immigration debate on economic grounds.

“Labor shortage issues are rampant right now,” said Higgins. “Part of the problem is that right now the American people don’t associate that labor shortage with the need for immigrants. So one thing that we need to be doing better is correlating those two. And doing more to combat some of the arguments from the far right that increased immigrant labor lowers American wages.”

In his widely cited 2011 paper, “Rethinking the Effect of Immigration on Wages,” economist Giovanni Peri found that large inflows of immigrants to American cities left unchanged or increased the wages for American workers. And Higgins went on to say that in order to fully realize recent bipartisan laws meant to bolster the economy, like the CHIPS Act, more immigrant labor will be needed.

Rep. Jimmy Panetta, a Democrat whose congressional district includes California’s central coast, told Ideaspace that he sees the Farm Workforce Modernization Act as the top priority for immigration legislation in the Republican-led House, precisely because of its appeal to GOP concerns. According to a September report by the Cato Institute, the bill’s reforms of the H-2A minimum wage rules (which presently limit the number of workers hired), would reduce agricultural labor costs by roughly $1 billion in the first year and $1.8 billion in the second year, “which would lead to more workers hired, more productivity, and lower prices for consumers.” Beyond addressing inflation for all Americans, the bill would most directly benefit rural America, where the GOP is dominant.

Rep. Jimmy Panetta, a Democrat whose congressional district includes California’s central coast, told Ideaspace that he sees the Farm Workforce Modernization Act as the top priority for immigration legislation in the Republican-led House, precisely because of its appeal to GOP concerns. According to a September report by the Cato Institute, the bill’s reforms of the H-2A minimum wage rules (which presently limit the number of workers hired), would reduce agricultural labor costs by roughly $1 billion in the first year and $1.8 billion in the second year, “which would lead to more workers hired, more productivity, and lower prices for consumers.” Beyond addressing inflation for all Americans, the bill would most directly benefit rural America, where the GOP is dominant.

“There are plenty of Republican members who are willing to lean into this type of bill, that obviously helps the economy [in their home districts],” said Rep. Panetta. To obtain passage out of the House, a bill with 100 percent of House Democrats signed on would only need five House Republicans. “And this is the kind of bill that’s prime for doing that. It’s basically the most bipartisan bill to pass out of the House of Representatives when it comes to immigration reform in, I think, the past few decades.” (In the Democratically-led 117th Congress, the bill passed overwhelmingly, 247-174, but later stalled in the Senate.)

Though Rep. Panetta is confident that plenty of Republican support remains in the 118th Congress for the Farm Workforce Modernization Act, he concedes that it is unlikely House Republican leadership will allow the bill to make it out of committee and receive a floor vote.

“Knowing who is going to chair the Judiciary Committee, the anti-immigrant sentiment by some of the Republican House leadership, I do believe it’s going to be very difficult to have regular order going through committees,” said the congressman. “Therefore, I believe the discharge petition will come into play on moving immigration bills.”

The discharge petition is a rarely-used congressional maneuver allowing rank-and-file members to bypass House leadership and force a floor vote on a piece of legislation if a majority of House members sign on. The discharge petition was famously used by Pres. Lyndon Johnson and his House allies to force a floor vote on the Civil Rights Act, but has only been used successfully four times since 1985. This is because members of the majority party are hesitant to embarrass their leadership by signing on to a discharge petition. But Speaker McCarthy’s tenuous hold on power may deem him uniquely vulnerable to the maneuver. Still, Rep. Panetta says that even with a weak House speaker, members will be wary of bucking leadership for fear of political retribution, like loss of committee assignments or withholding of support by the national party come election time.

The discharge petition is a rarely-used congressional maneuver allowing rank-and-file members to bypass House leadership and force a floor vote on a piece of legislation if a majority of House members sign on. The discharge petition was famously used by Pres. Lyndon Johnson and his House allies to force a floor vote on the Civil Rights Act, but has only been used successfully four times since 1985. This is because members of the majority party are hesitant to embarrass their leadership by signing on to a discharge petition. But Speaker McCarthy’s tenuous hold on power may deem him uniquely vulnerable to the maneuver. Still, Rep. Panetta says that even with a weak House speaker, members will be wary of bucking leadership for fear of political retribution, like loss of committee assignments or withholding of support by the national party come election time.

In addition to Speaker McCarthy’s weak position, however, the Republican House majority also includes members who represent congressional districts that Joe Biden won in 2020, where it may be politically prudent to go against Republican leadership on a bill with popular support. In New York state, for example, where agriculture is heavily reliant on immigrant workers, Republicans represent six congressional districts that favor the Democratic president.

“And you don’t just see it in New York,” said Rep. Panetta. “You see it here in California. Rep. David Valadao sees the value of immigrants to his community and his economy. And there are Republicans like Dan Newhouse of Washington state and Michael Simpson of Idaho who are not just willing to vote, but willing to lead in negotiations in formulating the bill.”

The White House itself is reportedly targeting 18 Republicans currently representing congressional districts that Biden won in 2020. According to CNN, aides to Pres. Biden “are putting together plans to squeeze and shame them in the hopes of peeling off a few key votes over the next two years.”

While comprehensive immigration reform appears to be far from the minds of House Democrats, at least for the next two years, sophomore House Republican Maria Elvira Salazar is looking to go big on immigration in the 118th Congress. According to John-Mark Kolb, Rep. Salazar’s deputy chief of staff, the Florida congresswoman’s Dignity Act will “solve the multiple problems connected to immigration all at once.”

While comprehensive immigration reform appears to be far from the minds of House Democrats, at least for the next two years, sophomore House Republican Maria Elvira Salazar is looking to go big on immigration in the 118th Congress. According to John-Mark Kolb, Rep. Salazar’s deputy chief of staff, the Florida congresswoman’s Dignity Act will “solve the multiple problems connected to immigration all at once.”

First introduced in the 117th Congress and soon to be reintroduced in the 118th, the Dignity Act would provide a path to legalization for the roughly 11 million undocumented immigrants currently residing in the United States. It would also provide additional funding for border security and border infrastructure, mandate the E-Verify program nationwide, establish regional processing centers at the border for asylum claimants, hire more immigration court personnel, and address the root causes of immigration in Central America, among other provisions.

The bill has much in common with previous “grand bargains” on immigration: relief for those undocumented individuals who are already in the United States in exchange for a robust border security policy that aims to effectively shut the door behind them. But the chief innovation of the Dignity Act, one that Rep. Salazar believes will be appealing to Republicans, is that it stops short of citizenship and what the GOP has come to disparage as amnesty.

“The rhetoric in some of the bills that have come out of the Democratic Party has been: you either give them immediate citizenship or nothing — there’s no middle ground,” said Kolb. “And she argues in the Dignity Act, what we do is legalize people first. So you take away the immediate problem of they’re scared to get deported, and also you allow them to legally work.”

In addition to falling short of citizenship, participants in the Dignity Program would not have access to means-tested benefits or entitlements, and would be required to pay restitution to the U.S. government for having broken the law. Over the course of the ten-year program, participants would pay the U.S. government $10,000 (or $2,000 every two years), all the while being permitted to legally work and reside in the U.S. Those fees would be placed in a fund dedicated to job training for native-born workers. This is intended to address the concerns of Republicans who believe that immigrants usurp jobs from Americans despite academic research that undercuts this intuitive belief and points to a more complex relationship. Upon completion of the 10-year program, participants would be granted legal permanent residency and could then avail themselves of an optional 5-year path to citizenship.

In addition to falling short of citizenship, participants in the Dignity Program would not have access to means-tested benefits or entitlements, and would be required to pay restitution to the U.S. government for having broken the law. Over the course of the ten-year program, participants would pay the U.S. government $10,000 (or $2,000 every two years), all the while being permitted to legally work and reside in the U.S. Those fees would be placed in a fund dedicated to job training for native-born workers. This is intended to address the concerns of Republicans who believe that immigrants usurp jobs from Americans despite academic research that undercuts this intuitive belief and points to a more complex relationship. Upon completion of the 10-year program, participants would be granted legal permanent residency and could then avail themselves of an optional 5-year path to citizenship.

“The key here is that they are earning it, and that’s what Republicans want,” said Kolb. “We think the proposal to immediately grant citizenship, like the U.S. Citizenship Act, didn’t have close to the votes. And that was in a House that was controlled by the Democrats.”

It remains to be seen if the Dignity Act can garner the necessary support from House Republicans, let alone from House Democrats (in the 117th Congress, the bill attracted a total of seven Republican cosponsors and zero Democrats and never made it to the House floor for a vote). In any event, Rep. Salazar is a novel figure in the immigration debate: a sophomore Republican emerging from Florida, an ascendant power center in Republican politics, who is also a Latina representing a growing constituency in the GOP, offering a proposal that would bring 11 million undocumented immigrants out of the shadows overnight (a top priority for the Democratic Party). All told, it has the potential to upend the conventional calculus for immigration reform. In a highly polarized House led by the Republican Party, the Dignity Act has a better shot than any comparably ambitious Democratic proposal of making it to a floor vote in the 118th Congress.

Morad Ghorban, who oversaw the drafting of the Temporary Family Visitation Act and is leading the effort to turn the bill into law, believes the path to success for immigration legislation in the 118th Congress may have to start in the Senate.

“My sense is that early on the focus of the House is going to be on messaging bills and measures that would secure the border,” said Ghorban, director of government relations and policy for The Public Affairs Alliance of Iranian Americans (PAAIA). “And we know that in the last Congress, there were discussions being had between Republican and Democratic lawmakers on the Senate Judiciary Committee about smaller bipartisan proposals like ours that could reach that 60-vote [filibuster] threshold. My understanding is that these discussions are going to continue in the 118th Congress.

“My sense is that early on the focus of the House is going to be on messaging bills and measures that would secure the border,” said Ghorban, director of government relations and policy for The Public Affairs Alliance of Iranian Americans (PAAIA). “And we know that in the last Congress, there were discussions being had between Republican and Democratic lawmakers on the Senate Judiciary Committee about smaller bipartisan proposals like ours that could reach that 60-vote [filibuster] threshold. My understanding is that these discussions are going to continue in the 118th Congress.

“So I think as far as a shift in strategy,” continues Ghorban, “we’re putting more focus on the Senate where bipartisan consensus or solutions can be had; with the hopes that if you see some of these measures starting to be moved on in the Senate, it could trigger action by the House.”

Dip Patel plays a similar role to Ghorban on the America’s Children Act. That bill would provide a pathway to permanent residency for “Documented Dreamers,” who are stunned to find that having grown up as documented children, they face deportation upon turning 21. They are not eligible for DACA because they were brought to the U.S. legally on their parents’ visa. Patel agrees that the road to success for immigration legislation in the 118th Congress likely begins in the Senate.

“It’s going to be incredibly difficult to start in the House, but we have to continue to advocate all options,” said Patel, who founded the nonprofit organization Improve the Dream to advocate for Documented Dreamers. “Sen. Tillis and Sen. Sinema came close on immigration at the end of last year, and it seems they’re continuing those conversations. Hopefully something like that, which should include Documented Dreamers, can pass out of the Senate, which would create pressure on moving it in the House.”

Patel is hoping that, early on, this Congress will give broader reforms a vote. His thinking is two-fold: 1. If it’s successful, great. 2. If it fails, lawmakers can then recognize that comprehensive reform is presently unattainable and start to move on small measures with bipartisan support.

Patel is hoping that, early on, this Congress will give broader reforms a vote. His thinking is two-fold: 1. If it’s successful, great. 2. If it fails, lawmakers can then recognize that comprehensive reform is presently unattainable and start to move on small measures with bipartisan support.

“Over the last 20 years, imagine if every year we were able to get a narrow improvement in the immigration system,” said Patel. “Every year, a narrow improvement. That, essentially, by now, would’ve taken care of most of what we want in comprehensive reform.”

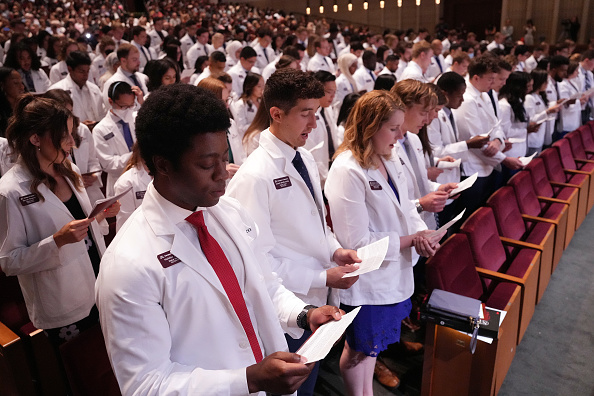

Patel’s optimism notwithstanding, experts on the politics of the House appear resigned to an immigration stalemate in the 118th Congress, unless some sort of crisis point emerges in the next two years. Sources from both sides of the aisle believe Congress may find that crisis point in an anticipated U.S. Supreme Court decision outlawing DACA, or the Deferred Action on Child Arrivals program, which grants protection from deportation and work authorization in two-year blocks to undocumented immigrants who were brought to the country as minors — commonly known as Dreamers. It’s estimated that upwards of 600,000 individuals currently avail themselves of the program.

In the wake of Congress’s failure to find a way to grant legal status to Dreamers, Pres. Barack Obama created the DACA program in 2012. It has operated precariously ever since. After the Trump administration terminated DACA in 2017, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2020 that Trump’s action was “arbitrary and capricious” and allowed the program to stay in place, but the court did not rule on the legality of the program. Pres. Biden has attempted to refortify the program, but in 2021 a Texas-based U.S. district judge ruled DACA illegal, on the basis that it grants immigration benefits that require congressional action, and ordered the Department of Homeland Security to stop approving new applications. In October of last year, a federal appeals court agreed that DACA was illegal, but sent the case back to the district judge for review of a new rule issued by the Biden administration. The case appears to be headed to the U.S. Supreme Court, where a 6-3 conservative majority may be primed to outlaw DACA.

“You know, in 2018 we thought the Supreme Court was gonna take up the DACA case, and they declined to do so,” said Casey Higgins, the former staffer to Speaker Ryan. “But that concern made us move. We started putting immigration legislation on the floor. It all failed … but that was the impetus for action. I think that there’s a world in which, as this DACA case approaches, as the border becomes more unruly, there is at some point going to be an inflection point, that both sides have to come together, and they have to do something, because there’s overwhelming political pressure saying, ‘This must be done.’ I’m praying that it does not take visual of DACA kids being deported to force that to happen, but we are very much at the point that I think we’re waiting for a crisis point and that will prompt action. And it will be border/DACA action.”

“You know, in 2018 we thought the Supreme Court was gonna take up the DACA case, and they declined to do so,” said Casey Higgins, the former staffer to Speaker Ryan. “But that concern made us move. We started putting immigration legislation on the floor. It all failed … but that was the impetus for action. I think that there’s a world in which, as this DACA case approaches, as the border becomes more unruly, there is at some point going to be an inflection point, that both sides have to come together, and they have to do something, because there’s overwhelming political pressure saying, ‘This must be done.’ I’m praying that it does not take visual of DACA kids being deported to force that to happen, but we are very much at the point that I think we’re waiting for a crisis point and that will prompt action. And it will be border/DACA action.”

Mark Krikorian, executive director of the Center for Immigration Studies, a leading think tank in the country’s immigration reduction movement, agrees with Higgins that the outlawing of DACA could force congressional action. He also sees a world in which a DACA ruling could dovetail with a critical moment at the border, where U.S. authorities encountered more than 2 million migrants in fiscal year 2022, “especially if there’s some kind of news-grabbing event, like the Haitians parked under the bridge a couple of years ago in Del Rio, Texas.”

Under such circumstances, Krikorian envisions the Democrats trading narrow elements of border security for a small fix to DACA. “That’s the one wild card that could change the prediction that nothing’s going to reach the president’s desk,” he said. “It is at least possible that you would then end up with a ‘mini bargain.’ Which is okay, because that’s the way legislation is supposed to work, for heaven’s sake. It’s not all 2,000-page bills where you ‘solve’ everything. A prudent approach to legislating is each side gets a little bit and sees how it works, and then maybe you come back and each side gets a little more.”

Read More:

Congressional Note No. 2