Growing up in central Illinois, Dip Patel never questioned his immigration status. He knew he was born in Ghandinagar, India, but otherwise he felt like a typical American kid. His parents owned and operated a convenience store; he listened to American music, watched American movies, and enjoyed playing tennis and soccer.

“I just went about my life as any child growing up in America would; I felt the same as my American peers,” Patel, now 26 years old, told Ideaspace.

It wasn’t until he was 15 years old, when he enrolled in a driver’s education course at his local Illinois high school, that Patel realized his American experience wasn’t so typical. When it came to filling out the learner’s permit application, Patel was flummoxed when it asked for his social security number.

It wasn’t until he was 15 years old, when he enrolled in a driver’s education course at his local Illinois high school, that Patel realized his American experience wasn’t so typical. When it came to filling out the learner’s permit application, Patel was flummoxed when it asked for his social security number.

“What do you mean you don’t have a social security number?” his teacher asked him.

“And this was just the beginning,” Patel recently recalled. “I would soon find out that my lack of a social security number would prevent me from getting a job, would prevent me from qualifying for in-state college tuition, and that at age 21, I would age out of my parents’ visa and be subject to deportation.”

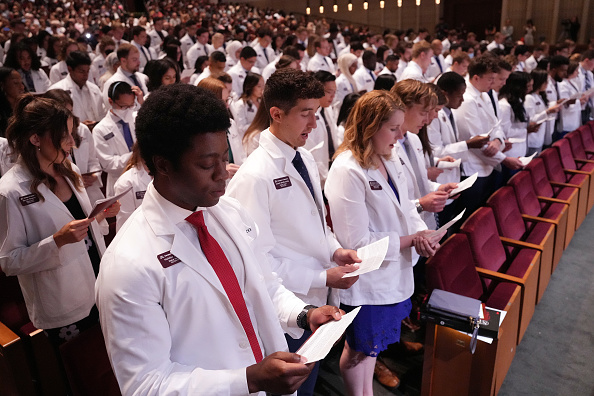

Patel is among the country’s more than 200,000 children of long-term visa holders, who, upon turning 21, age out of their parents’ visa protections and are treated no differently than an undocumented immigrant. The one difference is that, because they were documented as minors, they are not eligible for DACA protections and would not benefit from passage of the DREAM Act, which only apply to undocumented minors. Oftentimes, these “Documented Dreamers” attend an American university on a student visa, but once they graduate and enter the workforce, they must obtain an employment-based visa as a foreign national or self-deport to a country with which they have little to no connection.

Patel’s family moved from India to Canada when he was four years old, and landed in Illinois when he was nine. By virtue of his family having lived in Canada, Patel, who holds a doctorate degree from the University of Health Sciences and Pharmacy in St. Louis, is able to work as a pharmacist at an Illinois hospital under the USMCA — the updated NAFTA trade agreement that allows qualified Canadians to work in the U.S. in specific professional occupations. But most Documented Dreamers do not benefit from such reprieves. Seventy percent are Indian nationals, according to Improve the Dream, the nonprofit organization that Patel founded to advocate for Documented Dreamers. With a per-country cap that limits Indian nationals from obtaining more than 7 percent of available employment-based visas in a given year, they often face deportation.

Patel’s family moved from India to Canada when he was four years old, and landed in Illinois when he was nine. By virtue of his family having lived in Canada, Patel, who holds a doctorate degree from the University of Health Sciences and Pharmacy in St. Louis, is able to work as a pharmacist at an Illinois hospital under the USMCA — the updated NAFTA trade agreement that allows qualified Canadians to work in the U.S. in specific professional occupations. But most Documented Dreamers do not benefit from such reprieves. Seventy percent are Indian nationals, according to Improve the Dream, the nonprofit organization that Patel founded to advocate for Documented Dreamers. With a per-country cap that limits Indian nationals from obtaining more than 7 percent of available employment-based visas in a given year, they often face deportation.

“I came here when I was nine,” said Patel. “But the average age of a Documented Dreamer [on arrival] is five. And there are so many who came here when they were babies. How are they expected to be anything but American?”

Through his Improve the Dream nonprofit, Patel is one of the leading advocates for the America’s Children Act. The bill, which was introduced in both the Senate and the House last year, would establish a pathway to permanent residency for Documented Dreamers, provided they are college graduates and have maintained legal status in the U.S. for 10 years. The bill would also provide age-out protections and work authorization for Documented Dreamers with pending green card applications. Thus far the Senate bill, introduced by Democratic Sen. Alex Padilla of California, has six Republican and four Democratic cosponsors, as well as Independent Sen. Angus King of Maine. Meanwhile, the House bill boasts 11 Republican and 33 Democratic cosponsors.

Rep. Deborah Ross, the Democrat from North Carolina who introduced the House bill, is not surprised by the strong support the legislation has garnered from Republicans, who, as a party, have otherwise grown increasingly anti-immigration in the Trump era.

Rep. Deborah Ross, the Democrat from North Carolina who introduced the House bill, is not surprised by the strong support the legislation has garnered from Republicans, who, as a party, have otherwise grown increasingly anti-immigration in the Trump era.

“The Republicans who are more business-oriented completely understand the contributions that immigrants have made to this country, and the need right now for talent from the best and the brightest from all over the world,” the congresswoman told Ideaspace, adding that these children of long-term visa holders are “rock-star kids” — 87 percent of whom are STEM graduates.

“One of the arguments I make that is very compelling to my Republican colleagues is that if we deport 21- and 22-year-olds who we have paid to educate, who are very motivated to be in this country, they’re going to work for our competitors internationally and we’re not going to benefit from the innovation. We’re going to fall behind.”

You can hear Rep. Ross’s sentiment echoed in comments made earlier this year by Sen. Thom Tillis, Republican of North Carolina, at a Senate subcommittee hearing on removing barriers to legal immigration.

“I’ve tried to tell anyone who thinks that we just need to find more computer scientists, more data analysts, more people with advanced degrees from the U.S. population that they need to wake up and recognize,” said Sen. Tillis, “if we want our economy to continue to grow, if we want to continue to build on this great economy, that we’ve got to look to legal immigration as a critical part of fulfilling our workforce needs and really growing our innovation economy.”

Nevertheless, opposition in the House Republican caucus to expanding immigration benefits remains strong, largely in the name of prioritizing border security. Last April, at a House Judiciary committee hearing on Homeland Security Oversight, in which Rep. Ross forcefully advocated on behalf of Documented Dreamers, Republicans rarely strayed from talking about the record number of migrants and the scourge of fentanyl coming to the southern border. Rep. Jim Jordan, Republican of Ohio, summed up such sentiments at the hearing thusly: “Americans want legal immigration. President Biden and Secretary Mayorkas want illegal immigration.”

Nevertheless, opposition in the House Republican caucus to expanding immigration benefits remains strong, largely in the name of prioritizing border security. Last April, at a House Judiciary committee hearing on Homeland Security Oversight, in which Rep. Ross forcefully advocated on behalf of Documented Dreamers, Republicans rarely strayed from talking about the record number of migrants and the scourge of fentanyl coming to the southern border. Rep. Jim Jordan, Republican of Ohio, summed up such sentiments at the hearing thusly: “Americans want legal immigration. President Biden and Secretary Mayorkas want illegal immigration.”

While advocates of the America’s Children Act are wary of creating a system that favors the documented over the undocumented, they point out that Documented Dreamers are unfairly excluded from DACA and the DREAM Act, and hope that the Republican notion of supporting legal immigration, as expressed by Rep. Jordan, can help their cause.

As for the expired legal status of Documented Dreamers, Rep. Ross points out that when they arrived here legally as minors, there was no expectation they would face deportation once they aged out of their parents’ visa protections.

“Ten years ago, it wasn’t a problem for Documented Dreamers because they were getting their visas,” she said.

The problem is that over the last decade immigration demand has grown exponentially, creating a backlog of 1.4 million individuals vying for an employment-based visa — and Congressional Research Service recently estimated the backlog could exceed 2 million by the year 2030. In the current system, only 140,000 employment-based visas are awarded annually. Because the children and spouses of visa recipients count against the total, only 70,000 visas are going to eligible workers.

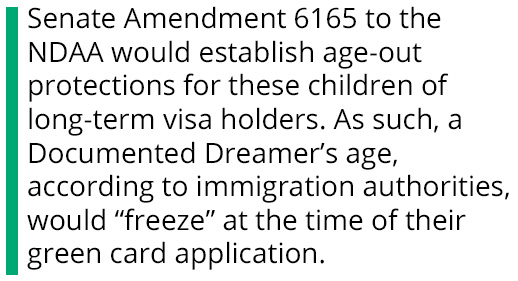

For Documented Dreamers, a reprieve could come in the form of Senate Amendment 6165 to the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023, to be voted on by Congress in the lame-duck session. The amendment — introduced by Sen. Padilla and cosponsored by five Republicans, including Sens. Rand Paul, Roy Blunt, and Mike Rounds — would establish age-out protections for these children of long-term visa holders. As such, a Documented Dreamer’s age, according to immigration authorities, would “freeze” at the time of their green card application.

For Documented Dreamers, a reprieve could come in the form of Senate Amendment 6165 to the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023, to be voted on by Congress in the lame-duck session. The amendment — introduced by Sen. Padilla and cosponsored by five Republicans, including Sens. Rand Paul, Roy Blunt, and Mike Rounds — would establish age-out protections for these children of long-term visa holders. As such, a Documented Dreamer’s age, according to immigration authorities, would “freeze” at the time of their green card application.

When asked if this narrow measure in the NDAA could undermine support for the America’s Children Act, Rep. Ross emphatically said no.

“I see it as this fantastic opportunity to build more awareness and more support among Republican senators,” she said. “I frankly cannot believe how quickly this issue has converted people on some of these immigration issues. And so I see it as a perfect way to educate people and have them start to look for common-ground solutions.”

Patel agrees that the more Republican lawmakers learn about the plight of Documented Dreamers, the higher the likelihood of bipartisan consensus in Congress. “When a Documented Dreamer turns 21, it’s like stepping foot here for the first time ever,” he said. “That’s just the craziest part of this whole thing. There’s no prioritization for children of immigrants who grew up here legally. And I think most people would be surprised by that.”

Read More:

Congressional Note No. 2