Views expressed by any party interviewed by Ideaspace are those of the interviewee and are not necessarily shared by Ideaspace.

The following is a transcript of the video briefing above, lightly edited for clarity and presented here to enable users to search the participants’ comments.

DW Gibson:

Today we’re talking about the asylum process. Why has the number of applicants risen so dramatically in recent years and what policies might improve the adjudication process to address the mounting backlog of cases? We’re grateful to have Aaron Reichlin-Melnick with us here today to help us address these questions. Aaron is the policy director at the American Immigration Council, where he directs the council’s administrative and legislative advocacy efforts to provide lawmakers, policymakers, advocates, and the general public with accurate and timely information about the role of immigrants in the United States.

He previously served as Senior Policy Counsel, where he worked primarily on border and immigration court cases and the intersection of immigration law and policy. He has also worked as a staff attorney at the council and prior to joining the council, he was an Immigrant Justice Corps Fellow placed as a staff attorney at the Immigration Law Unit of the Legal Aid Society of New York City. Aaron holds a JD from Georgetown University Law Center and a BA in politics and East Asian studies from Brandeis University. We’re glad to have you with us today, Aaron. Thanks for joining us.

Aaron Reichlin-Melnick:

Thank you for having me.

DW Gibson:

I’ll get us started with sort of really a basic question, but I want to make sure we’re all on the same page. Could you please give us a very brief overview of how asylum is structured in this country in terms of the categories that are available to applicants? I think a lot of times we lose sight of just how focused our asylum opportunities are to enter the country.

Aaron Reichlin-Melnick:

Yeah. Unfortunately, when you ask me for something brief, I’m going to go a little bit beyond that and I want to start with a really brief overview of what is asylum. I want to make a point here that asylum is an ancient idea. The word itself comes from ancient Greek, and the idea is even older. The Old Testament even talks about cities of refuge, where people who unintentionally killed another could seek refuge and a trial that would potentially allow them to live in that city of refuge, safe from their persecutors if a court determined that they had indeed killed someone unintentionally.

Of course the modern concept of asylum is very different. It arises out of World War II and the Holocaust and everything that went on there. The 1951 Convention of Refugees established what are known as the five protected grounds that any person can get asylum or refugee status for. Those grounds are specifically race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, and political opinion. When the United States joined in these international treaties and eventually codified them into law in the 1980 Refugee Act, it created the bones of the system we have today, which were all centered around this idea of determining whether or not a person fell into those five categories, whether that person faced persecution on account of their race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.

So our modern asylum system is based around determining whether any particular applicant falls within one of those five categories. Importantly, those five categories are limited and they are a 20th century invention. Modern concepts of refugee status have expanded internationally, but the United States really does stick to a much more narrow definition of those terms than many other countries. When we talk about somebody applying for asylum, it means that even if an immigration judge determines that a person is going to be killed in their home country, they still may not qualify for asylum unless they are going to be killed for one of those five reasons.

In fact, under the Real ID Act of 2005, it has to be one central reason for their persecution. So this leads to a situation where you can have immigration judges saying, “I understand that you’re going to be killed most likely when you go back to your home country, but you’re just going to be killed for the wrong reasons. I’m sorry.” So that gives you some sense of how narrow the asylum conception is. Even, for example, armed conflict is not normally a ground for asylum and it can be the case that a person’s home country is being riddled by war, death squads, and everything like that, but if it’s just a war, that’s not a reason for that person to be granted asylum or refugee status in the United States. It just doesn’t count because it doesn’t fall within one of those five narrow categories.

In fact, under the Real ID Act of 2005, it has to be one central reason for their persecution. So this leads to a situation where you can have immigration judges saying, “I understand that you’re going to be killed most likely when you go back to your home country, but you’re just going to be killed for the wrong reasons. I’m sorry.” So that gives you some sense of how narrow the asylum conception is. Even, for example, armed conflict is not normally a ground for asylum and it can be the case that a person’s home country is being riddled by war, death squads, and everything like that, but if it’s just a war, that’s not a reason for that person to be granted asylum or refugee status in the United States. It just doesn’t count because it doesn’t fall within one of those five narrow categories.

DW Gibson:

That’s really eye-popping, especially that example you give of death might be on the line, but it might not be for the right reasons. I think that really calibrates our understanding of how narrow this passage is. That said, we have a lot of people trying to get through this opening, right? So right now I think our pending cases are somewhere in the neighborhood of 667,000 cases. This is part of a bigger backlog in immigration courts of 1.8, almost 1.9 million cases altogether, right? But focusing on asylum, over 600,000 cases pending and we’ve had historically a lot of cases year after year, but the last few years, some steep increases in applicants. Talk about that. What do you think is driving more and more people to try to get through this narrow opening?

Aaron Reichlin-Melnick:

Well, it’s actually over a million asylum applications because that number you gave, the over 660,000 or so, that’s only those cases in immigration courts. There’s an additional 460,000 people who have applied for asylum affirmatively with U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. So when you combine it together, you’re getting closer to 1.1 million pending asylum applications.

I think there’s a number of reasons for the rise. First is the fact that the idea that asylum is this narrow concept is not well known around the world.For most people, the idea of asylum and refugee status is about protection. This is in part due to the way that the refugee process works abroad and the fact that there is the colloquial refugee and then there is the refugee that falls into these five narrow categories. So when we talk about refugees, we are often not specifically referring to just people who qualify under those five grounds. We’re often just talking about people who are fleeing their home countries because of violence, instability, and all the reasons that make them feel that they just can’t stay anymore.

So as a result, the asylum process, there’s a lot of people who have applied for asylum who aren’t going to win their cases. Now you hear from many people who say, “This is because it’s fraud. They all know this. But I’ve talked to dozens, if not hundreds, of asylum seekers over the course of the last eight years and most people, they don’t know that. They know that the United States is a place that they view as safe and secure from the problems that they’re fleeing and when they arrive at the border, they know that asylum is the way to ask for protection.

So for a lot of people, they just simply don’t know that they’re not going to fall within those narrow categories and our system is set up such that people have a chance to apply anyway. We err on the side of caution. As to why the numbers have gone up in recent years, there’s a lot of different factors that go into that, but really the largest issues are the root causes. There’s a lot of talk about pull factors on the side of the United States. People say, “It’s U.S. policy drawing people here.” But there’s really not a lot of evidence behind that. In fact, if you look at the first wave of asylum seekers in 2014, you can trace that pretty directly to major rises in violence and impunity in Central America.

Since then things have shifted. Things are changing. Today people are coming from countries that they haven’t been coming from for decades. Over the last 18 months, for example, there have been more than half a million asylum seekers from Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua, countries that in the past, with the exception of Cuba, have not sent large numbers of refugees to the United States. There have been smaller waves. For example, Nicaraguans in the 1980s fled to the United States and sought asylum a lot during political struggles. Cubans of course have come in various waves over the years, especially, for example, the Mariel boatlift in the 1980s, but just in the last six months alone, more Cubans have shown up at the border asking for protection than came during the entire Mariel boatlift in 1980.

Since then things have shifted. Things are changing. Today people are coming from countries that they haven’t been coming from for decades. Over the last 18 months, for example, there have been more than half a million asylum seekers from Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua, countries that in the past, with the exception of Cuba, have not sent large numbers of refugees to the United States. There have been smaller waves. For example, Nicaraguans in the 1980s fled to the United States and sought asylum a lot during political struggles. Cubans of course have come in various waves over the years, especially, for example, the Mariel boatlift in the 1980s, but just in the last six months alone, more Cubans have shown up at the border asking for protection than came during the entire Mariel boatlift in 1980.

So we are in a situation now where we have a combined flow of refugees that are coming for a wide variety of reasons from different places as well. It’s not like we’re the only country getting this. This is really important to note. Costa Rica, for example, south of Nicaragua, the country directly south of Nicaragua, has seen the highest number of Nicaraguans applying for refugee status in that country ever. I believe it’s 50 to 60,000 applications just in the last year or two. So while some people are coming to the United States, other people are going elsewhere.

We talk about Venezuelans, for instance. More than 6 million Venezuelans have left the country over the last five or six years. The overwhelming majority of them are in the surrounding countries around Venezuela, but as the situation in Venezuela continues and instability and economic conditions in the surrounding countries get worse, refugees are in a precarious situation and if they don’t have a permanent place to go, then they are more likely to try to find somewhere else that’s safer. In the last 18 months or so, we’ve seen this with Venezuelans and we’ve seen this with Haitians, when about 100,000 Haitians who left the country after the 2010 earthquake have made their way to the U.S.-Mexico border in large part because they were being kicked out of the countries that they had been staying in due to a rise in xenophobia and anti-migrant sentiment during the COVID-19 pandemic and the related economic troubles.

So you really can’t point to one thing going on. It is really a wide variety of factors. It’s global economic difficulties. It is the COVID-19 pandemic and the concordant rise in xenophobia south of the border that has displaced refugees who are already in other countries. It is the economic situation in the United States, which is a big draw. There’s no denying that. It’s also the increase in political crackdowns that have been occurring in a number of countries, such as Nicaragua, Cuba, and Venezuela over the last 18 months or so. So it’s a lot and also its climate change.

For example, a large driver of Guatemalans to the border in recent months has been famine in the indigenous regions and many indigenous Guatemalans feel that they have no other choice but to come to the United States due to discrimination that occurs if they try to move into the cities. There is this migrant pathway that’s been created in those countries, and we are seeing more and more of that, but despite all the talk about migrants coming from afar, abroad, Africa, Asia, et cetera, that still remains relatively minor, less than 5 percent of the people coming to the border. Now, even 5 percent is much higher than it has been in previous years, but it isn’t like there are now millions of people coming from Asia or Africa. It is still primarily people from the Western Hemisphere and, in recent months, that increase has been seen among the Venezuelans, Cubans, Nicaraguas, and people who already have a lot of political reasons to be leaving.

For example, a large driver of Guatemalans to the border in recent months has been famine in the indigenous regions and many indigenous Guatemalans feel that they have no other choice but to come to the United States due to discrimination that occurs if they try to move into the cities. There is this migrant pathway that’s been created in those countries, and we are seeing more and more of that, but despite all the talk about migrants coming from afar, abroad, Africa, Asia, et cetera, that still remains relatively minor, less than 5 percent of the people coming to the border. Now, even 5 percent is much higher than it has been in previous years, but it isn’t like there are now millions of people coming from Asia or Africa. It is still primarily people from the Western Hemisphere and, in recent months, that increase has been seen among the Venezuelans, Cubans, Nicaraguas, and people who already have a lot of political reasons to be leaving.

DW Gibson:

So many of the factors that you just highlighted in terms of climate change and instability in other nation states point to the fact that we need to have international cooperation when it comes to addressing these issues, but let’s go back to the very beginning of your answer in terms of your experience talking to asylum applicants about what they understand regarding how limited these categories are. You made reference to other countries expanding how they define asylum categories. I wonder if you could tap into that more and talk about things we could do domestically in terms of policy, other avenues we could open up in terms of legal immigration that could take some of the strain off of the asylum process — even if it doesn’t feel politically feasible at the moment.

Aaron Reichlin-Melnick:

I think there is widespread agreement: the asylum process wasn’t designed for what we are seeing right now at the border. Part of that is just due to its age. There’s a couple of numbers I’d like to throw out here. One of them is 32 years. That’s how long it’s been since we made any major overhaul to our legal immigration system. The Immigration Act of 1990 passed in November of 1990 and that was one month before the first website went online. The worldwide web at that point hadn’t even come into existence. It was still just an idea in the brain of Tim Berners-Lee as he was setting it together.

We last upgraded our asylum system in 1996 in IIRAIRA, the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, which created the modern asylum office and the “credible fear” process that many people go through, but that is a solidly 20th century system that was operating in a time when the people coming across the border were overwhelmingly Mexican single adults looking for work. Today that is just not the case and our system is, not surprisingly, ill-equipped to handle that. Making matters worse, there have been years of neglect to the system of adjudication. So that, for example, the entire immigration court budget is about $600 million, though that number may be a little bit off. My apologies if it’s off by a hundred million.

Point is, however, the budget’s about a fifth the size of ICE, Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s budget. The Refugee and Asylum Office inside USCIS, that budget is being paid for by other immigrants applying for benefits — because USCIS is largely not congressionally funded, it’s a fees-based agency. That means that the agency’s never really been able to hire enough asylum officers to do what they need. So you have a situation where it’s years of systemic neglect in the adjudication side of things built over a framework that is decades old and does not respond to the modern world.

Point is, however, the budget’s about a fifth the size of ICE, Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s budget. The Refugee and Asylum Office inside USCIS, that budget is being paid for by other immigrants applying for benefits — because USCIS is largely not congressionally funded, it’s a fees-based agency. That means that the agency’s never really been able to hire enough asylum officers to do what they need. So you have a situation where it’s years of systemic neglect in the adjudication side of things built over a framework that is decades old and does not respond to the modern world.

At the same time, we know what is proven to reduce the number of people coming across the border and the answer is root causes work and expanding legal pathways. Today for the migrants who are showing up at the border, it’s pretty much a 99.9-percent guarantee that those people do not have a legal pathway to come to the United States, that no matter what those people did, they could not get a visa to come here. This has gotten even worse in recent years, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, when delays at consulates now are two to three years for some visa benefits. So even if someone might have a way to come here, it might take them two to three years to get that benefit and in that amount of time, they just decide they can’t do it.

Couple that with rampant misinformation that is being pushed by smugglers, and you get people who think that they can come here and get some sort of status or that the border is open, things like that, which are really not the case. You get this perfect storm where really very few people know what actual U.S. border policy is, but all they know is that there are no legal pathways and that if they come here, they’ll be allowed to stay for at least a few years while they go through the system. That is really a recipe for the situation we find ourselves in.

DW Gibson:

There’s a lot on the table now in terms of trying to fix some of the dysfunction you just described. There’s the Biden administration’s Interim Final Rule, there’s Representative Lofgren’s Real Courts, Rule of Law Act that she’s presented to reform immigration courts that might pertain to some of what we’re talking about. Start with the Biden administration’s rule changes. Talk to us about how you feel about those.

Aaron Reichlin-Melnick:

So there’s been a lot of attention paid to the Interim Final Rule that the Biden administration put out, their new asylum process. There’s a lot of misinformation about this rule, too. I just want to go over very quickly what the rule is and what it does. So this is a rule that applies only to people who go through the credible fear process, which is where a USCIS asylum officer evaluates whether a person has a credible fear of persecution, which, thanks to the Supreme Court, means about a 10-percent chance of being able to win their asylum case.

That is a deliberately low bar because when Congress passed it 1996, they said, “We really need to err on the side of caution.” I don’t want to get too much into the history, but there was a reason they wanted to do that because in the 1990s, there were a lot of scandals revealed about how the Reagan administration had been administering the asylum program over the course of the 80s and the H. W. Bush administration in the early 90s. INS had really scandalously been turning away 98 percent of Central American asylum seekers at a time of death squads and genocide against people from Central America.

Congress even eventually apologized for this through NACARA, the Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act. This was essentially coming out of a period where there had been, over the course of the nineties, a real recognition that the U.S. had screwed up in the treatment of asylum seekers in the 1980s, that it had turned away a lot of people who were sent back to death squads. So when Congress passed IIRAIRA in 1996, it recognized that it needed to create a low threshold so that it would err on the side of caution before sending people back to persecution.

Once people passed that credible fear process under the old system, they would just get sent straight to immigration court where they go into the backlogs of 1.8 million cases and a, maybe, four- to five-year wait. Under the Biden administration’s rule, instead of sending them straight to court, they would go first to an asylum officer and the asylum officer could determine whether or not that person qualifies for asylum and grant them asylum in a matter of weeks, as opposed to a matter of years.

Once people passed that credible fear process under the old system, they would just get sent straight to immigration court where they go into the backlogs of 1.8 million cases and a, maybe, four- to five-year wait. Under the Biden administration’s rule, instead of sending them straight to court, they would go first to an asylum officer and the asylum officer could determine whether or not that person qualifies for asylum and grant them asylum in a matter of weeks, as opposed to a matter of years.

There are some people who are saying asylum officers are bleeding heart liberals and are going to grant a lot more cases.The reality is that’s just not true. The asylum office grants asylum about twice as often as the immigration courts, but that’s largely a self-selection effect because people apply for the affirmative asylum usually if they think they have a chance of winning, but people in immigration court often apply for asylum defensively to avoid deportation. So you would expect to see, in other words, higher grant rates at the asylum office, especially because a lot of people who apply, who have visas and benefits and money and lawyers, who go through that process are more likely to win anyway.

So the idea that the asylum office is this bastion of liberalism that is going to be granting all of these cases is just nonsense. It doesn’t fit with the data and the facts, but nevertheless, the asylum process under this Interim Final Rule is fast. It is very fast. It is 60 days supposedly at the asylum office and then if you win, congratulations, you get asylum. If you lose, you go to the immigration court and that process is 60 to 90 days in the immigration court, is how fast it’s supposed to go. Max, 135 days under the regulations. That is quick. That is very quick. It’s quicker than the current system and it’s so quick that advocates have called on them to at least double the time because we think it’s so quick, people won’t even be able to get lawyers. We actually think that people sent to the immigration court under this new rule will be denied more often than under the current procedures, just because of how quick they’re pushed through the process.

So it is a rule that in theory can weed out the easy cases first, clear them off the docket and only send the more complicated cases to immigration court. Those more complicated cases, we are concerned that they’ll be denied more often under the rule, but it’s a little bit hard to say. The administration has said that they are listening to people who commented in response to the regulation and they may adjust the timelines when the final rule eventually comes down, but by no means is this rule a panacea. It will probably screen out the easy cases at the front end and let those people get asylum really quickly, but for pretty much everybody else, they are still going to the immigration court system, but now their cases are going to last a matter of months, not a matter of years.

DW Gibson:

DW Gibson:

So it sounds like a potential upside there in terms of weeding out those obvious cases, but it’s the backside that we need to keep an eye on in the coming months and years, in terms of denial rates for those cases that are kicked over to the courts. Two other policy issues that affect this discussion that remain live as we speak, and that are the Remain in Mexico policy and Title 42. Talk about those, and how you see the current state of both of those policies affecting the asylum process in the U.S.

Aaron Reichlin-Melnick:

As of Monday, the Remain in Mexico program is suspended. Judge Kacsmaryk lifted his injunctions following the Supreme Court’s order in June and a few hours later, the Department of Homeland Security announced that it was going to wind down MPP. There are still some open questions about whether those who were put back into Mexico in the first version of the program under the Trump administration will be again given another opportunity to reenter. There’s an ongoing question about whether or not Judge Kacsmaryk is going to do something else here because Texas has already filed a new request to temporarily set aside terminating the program a second time.

So we may still see some whiplash on this where we may see another court order seemingly stopping them from terminating the program. That could come in as early as a few weeks. We are still waiting to hear from Judge Kacsmaryk on what his timeline is going to be for deciding that motion, but as you mentioned, Title 42 is the big one in effect right now. I’ve said this many times: Title 42 is a failure of a policy on a wide variety of levels. That’s because right now there’s really two different phenomena going on at the border. Well, actually, let me take one step back.

The most important thing you have to know about programs like Title 42 and Remain in Mexico is that they fundamentally rely on Mexico in order to make them work and they also fundamentally are flawed because of the basic fact of all border enforcement policies. Once a person is on U.S. soil, even an inch on U.S. soil, that person is the United States’ problem. This is just how borders work in the modern world. Every country deals with this. So what that means is that once they’re on United States soil, if we want that person to leave United States soil, another country has to be willing to accept that person. So Remain in Mexico and Title 42 both rely on Mexico.

With Remain in Mexico, Mexico agreed to take a very limited number of people that come from the Western Hemisphere under the new version of the program, but if a person is from any country other than the Western Hemisphere, Mexico will not take that person. Title 42, when that went into place two years ago, Mexico said it would only take Salvadorians, Guatemalans, Mexicans, and Hondurans. It has, on an ad hoc basis, taken some other nationalities, but by and large, it is really only usable against those four nationalities.

What that means is if you come from one of those countries, the United States can expel you to Mexico, but if you don’t, if you come from Venezuela, Cuba, Nicaragua, for example, by and large, the United States cannot expel you to Mexico. So then the question is where could they expel you to? Well, Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua are also not accepting any U.S. Title 42 flights. So that means that if a Venezuelan steps onto U.S. soil, Mexico won’t take them and neither will Venezuela. At this point they become the United States’ problem, as it were, and we have no choice but to allow that person to access the asylum process, but importantly, even if we didn’t have an asylum process, that person would still not be deportable because there would be nowhere to send them.

What that means is if you come from one of those countries, the United States can expel you to Mexico, but if you don’t, if you come from Venezuela, Cuba, Nicaragua, for example, by and large, the United States cannot expel you to Mexico. So then the question is where could they expel you to? Well, Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua are also not accepting any U.S. Title 42 flights. So that means that if a Venezuelan steps onto U.S. soil, Mexico won’t take them and neither will Venezuela. At this point they become the United States’ problem, as it were, and we have no choice but to allow that person to access the asylum process, but importantly, even if we didn’t have an asylum process, that person would still not be deportable because there would be nowhere to send them.

In fact, this was the case for Cubans for decades. It was always the case. Since the 1980s, there was a 20-plus-year period where Cubans couldn’t be deported. Cuba would not take anyone, with some rare exceptions. What that meant is that even if a Cuban was ordered deported, eventually they’d just get released because the United States couldn’t do anything about it. This is a situation that we find ourselves in right now with Title 42. Single adult migrants from Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, have been overwhelmingly expelled back to Mexico — 1.5 million expulsions. By contrast, last month, I think 14 Venezuelans were expelled, total — out of 25,000 who came. Less than one tenth of 1 percent.

That gives you an example of why Title 42 is such a failure. For the groups that it is applied to the most — Mexican, Honduran, Guatemalan, El Salvador, and single adults — those are normally not people seeking asylum. Those are the people who are traditionally what would be called economic migrants or just people seeking a better life. They, under Title 42, cross the border over and over and over and over again, and just get expelled back to Mexico each time. Everyone else, Venezuelans, Cubans, Nicaraguans, et cetera, can’t be expelled under Title 42 because, by and large, their home countries won’t take them and neither will Mexico.

DW Gibson:

Nation states not taking planes is a real big factor. I want to throw one more question out to you and then I have a couple things in the chat that I want to get to, but one final question to you from me is this: As someone who looks at all this very carefully, and again, you’re aware of those circumstances that are big and international, climate change, relationships with other nation states, but again, drawing back down to a domestic setting, if you had the ear of the entire administration, all of Congress, what do you see out there in terms of changes, adjustments we could make that will start to alleviate the pressure on the adjudication process?

Aaron Reichlin-Melnick:

A surge of resources would be part of it. For example, three years of the immigration court system’s budget was about one year of Trump wall funding and walls don’t stop people from seeking asylum fundamentally because it’s very easy to get onto U.S. soil and a lot of the walls are built half a mile onto U.S. soil because you can’t build a wall in a floodplain. So walls don’t stop people from getting asylum. Instead we have poured billions of dollars into the wall, and we have not spent that money on creating a humanitarian protection system with the capacity to handle the amount of people that are coming through it now.

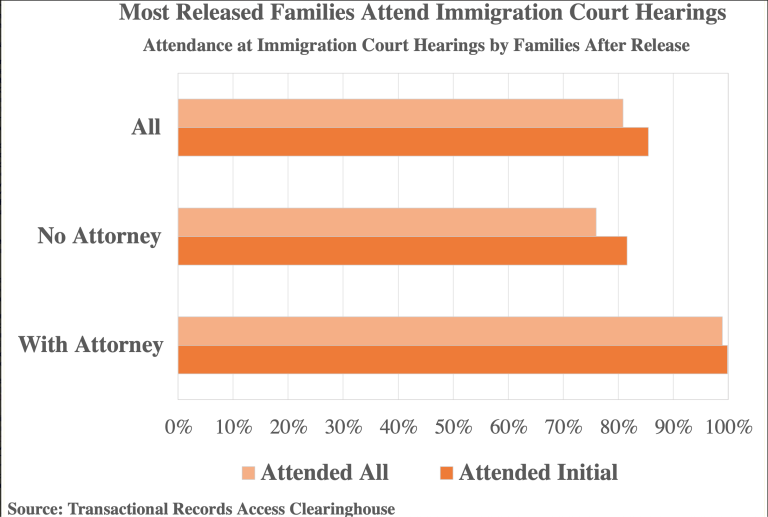

The other point I would make is that there’s a lot of research that shows when people believe they’ve been put through a fair process, they’re more likely to respect the outcome. I’m not going to pretend that every person who is ordered deported leaves the United States at the moment they’re ordered deported, but there’s a lot of good evidence in other countries as well, that when there is a clear process that people understand and that they feel that they have had a fair shot, they are far more likely to respect the process.

The other point I would make is that there’s a lot of research that shows when people believe they’ve been put through a fair process, they’re more likely to respect the outcome. I’m not going to pretend that every person who is ordered deported leaves the United States at the moment they’re ordered deported, but there’s a lot of good evidence in other countries as well, that when there is a clear process that people understand and that they feel that they have had a fair shot, they are far more likely to respect the process.

I also want to point to other countries and what they’ve done here. We are obviously not the only country to be dealing with this, but a lot of other countries provide a lot better assistance to migrants and refugees while they go through the process. In 1996, Congress envisioned that the process probably would take less than six months for most people and for decades it did. It didn’t start taking more than six months until really about the mid 2010s. So for about 15 years, or actually almost 20 years, they were largely correct that this was a short process and you didn’t need to do it, but today that process is taking four to five years and the system is not designed to do that.

You don’t get a work permit in most cases until about a year after you apply and during that time, you don’t have any real assistance or case management, whereas other countries, once you’ve made it into the process and you’re in the system, in Germany, for instance, there are reception centers where people go, where they learn German, where the federal government helps them find a job and work and let them integrate into the community while they go through the process so that people are not working under the table and subject to exploitation.

Today, we don’t have that kind of system in the United States. It’s really just nonprofits helping. That’s why the American Immigration Council and many other organizations have called for true case management programs that could actually help people find services, integrate into the community, and be able to go through this process without constantly living on the edge in insecurity. Unfortunately, this is another situation where once again that money is going to enforcement and it’s not going as much to case management as we’d like, even though I will say Congress has been increasingly funding case management programs, something that we greatly support, and we are just hoping for more money in the future.

Today, we don’t have that kind of system in the United States. It’s really just nonprofits helping. That’s why the American Immigration Council and many other organizations have called for true case management programs that could actually help people find services, integrate into the community, and be able to go through this process without constantly living on the edge in insecurity. Unfortunately, this is another situation where once again that money is going to enforcement and it’s not going as much to case management as we’d like, even though I will say Congress has been increasingly funding case management programs, something that we greatly support, and we are just hoping for more money in the future.

DW Gibson:

Funding is a big part of this. You mentioned that $600 million number for the immigration courts, which I know is a rough estimate. But we know in exact terms that ICE’s 2021 budget for detention was $2.9 billion. In these case management programs, we have data that shows us their efficacy in terms of people completing the process. I want to get to a question we have here from one of our audience members, and I’ll just read it to you. You characterize the U.S. definition of asylum and its asylum categories as very narrow compared with other countries. Can you give an example of another country that has a broader definition of asylum? So this taps into what you were talking about and asylum categories that are inclusive.

Aaron Reichlin-Melnick:

So this has largely to do with one of the most nebulous categories of those five, which is “a particular social group.” What does it mean to be a member of a particular social group? Well, a lot of countries have different views on that. In the United States, this has been a fairly limited definition. The Trump administration actually came in and cracked down on it and reduced the definition. Then the Biden administration came in and reversed it, once again expanding the definition to things like asylum for victims of domestic violence whose countries are unwilling or unable to protect them from domestic violence.

That’s something that is more common in other countries and in fact, when Biden took office, he signed an executive order calling for new regulations which would align the United States definition of particular social group with the U.N. handbook definition.

DW Gibson:

So that’s really the area where there’s opportunity there in terms of better defining some of the categories. You mentioned sexual orientation too, as a reason people are fleeing their homes.

Aaron Reichlin-Melnick:

Yes, sexual orientation is a great example of this. It took many years for sexual orientation to be recognized as a ground of protection under particular social group, but today that’s not a controversial thing. This is a way in which a particular social group is an expansive category that can be adapted as things change. When the Refugee Act of 1980 was passed, it was actually still illegal under U.S. law to immigrate to the United States if you were gay.

I think it was 1991 that they erased the bar on homosexuality from immigration law. It was a bar on mental diseases and it was under immigration law precedent, being gay was considered to be a disease and so therefore they would turn you away for it. When the Refugee Act was passed in 1980, Congress probably didn’t presume that it would later come to encompass people fleeing persecution on behalf of their sexual orientation, but today that’s not a controversial thing.

Similarly, victims of female genital mutilation are considered a protected category under U.S. law or those who oppose the one-child policy in China when it was still in existence. Those are good examples of the ways in which it has been expanded over the years. The Biden administration will hopefully get this regulation out sometime soon. It was supposed to come a year ago in October of 2021. It’s still not here and we are still waiting to see it and we hope that they’re continuing to work on it, but that’s a good example of the ways in which they could make it so that more people qualified, which would get more people permanence in the ability to stay here as an asylee.

Similarly, victims of female genital mutilation are considered a protected category under U.S. law or those who oppose the one-child policy in China when it was still in existence. Those are good examples of the ways in which it has been expanded over the years. The Biden administration will hopefully get this regulation out sometime soon. It was supposed to come a year ago in October of 2021. It’s still not here and we are still waiting to see it and we hope that they’re continuing to work on it, but that’s a good example of the ways in which they could make it so that more people qualified, which would get more people permanence in the ability to stay here as an asylee.

DW Gibson:

Aaron, you’ve been so helpful today and I hope that there’s been some clarity here for our audience, because I know this can be such a big, sprawling issue, but I think this point you’ve landed on here later in the conversation about appropriations and budgeting, I think it’s a place where we can see a way in, in terms of even just reorganizing the resources that are available to improve the system.

Aaron Reichlin-Melnick:

The American Immigration Council, we are not a lobbying organization. We are a 501(c)3, but we do a very small amount of lobbying and it is pretty much exclusively around the appropriations process. So if any of the offices here have questions about immigration appropriations, we are always happy to chat through. If anyone wants to reach out afterwards, we are open. Democratic or Republican, if you want to talk immigration, we want to talk through ideas, facts, figures, all of that. We’d love to chat.

DW Gibson:

Fantastic. Well, we appreciate you being with us here today. We appreciate everyone else for joining us and we’ll see you next time.

Aaron Reichlin-Melnick:

Thank you very much.

DW Gibson:

Take care.

Read More:

Congressional Note No. 2

Capitol Hill Briefing No. 7

Strategic Inquiry No. 8