Photo by John Moore/Getty.

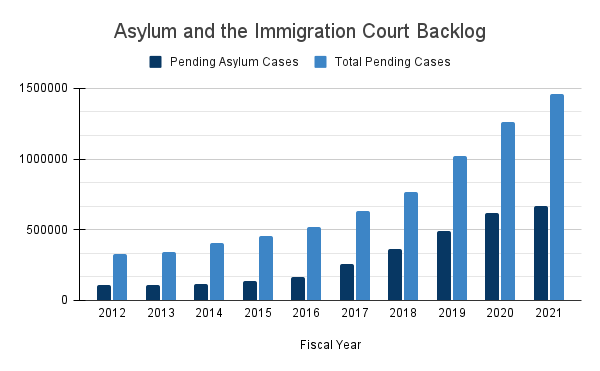

With 1,809,953 pending cases, the U.S. immigration court system is in crisis.

“If that was a population count, it’d be the fifth largest city in the country,” says Austin Kocher, a research assistant professor with Syracuse University’s Transactional Research Access Clearinghouse, a research institute that questions the legal rationale and everyday practices of the U.S. immigration court system. “And when I started using that analogy just a few years ago, it was the ninth largest city. The increases have been very recent and very dramatic.”

Consider that between 1998 and 2008, the number of pending cases increased by 43 percent; in contrast, over the last decade the number soared by nearly 450 percent.

Consider that between 1998 and 2008, the number of pending cases increased by 43 percent; in contrast, over the last decade the number soared by nearly 450 percent.

Different factors have driven the runaway numbers, but none more so than asylum claims. In 2012, there were 105,919 pending asylum cases in immigration court. Almost a decade later, in 2021, that number had risen to 667,229 cases, accounting for roughly 46 percent of all pending immigration court cases. (The others are deportation cases without asylum claims involved.)

Asylum adjudication is a multi-step process, involving several different federal offices — and it’s always in flux because of court rulings and varying priorities from one presidential administration to the next. The inherent complexities of the process allow for a wealth of misinformation and politically-motivated arguments that scuttle consensus-driven, practical fixes.

Ideaspace spoke with immigration experts to identify precise fixes that could make the U.S. immigration court system more efficient and provide relief for the infamous backlog. What follows is a close look at the causes for the dramatic increase in asylum applicants and a review of the politically feasible ideas for making asylum adjudication more effective.

Source: TRAC Syracuse University.

***

Asylum might just be the most misunderstood avenue for legally immigrating to our country. U.S. Code, Title 8, Section 1225 guarantees migrants the right to apply for asylum. As does the 1951 Geneva Convention, a U.N. multilateral treaty to which the U.S. is a signatory.

There are two types of asylum. Migrants can present themselves at a border or port of entry and make an asylum claim; these are known as affirmative asylum claims and are adjudicated non-adversarially by asylum officers from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). Immigrants who are going through deportation proceedings in immigration court can also file an asylum claim; these are known as defensive asylum claims and they are adjudicated adversarially, with a lawyer from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) representing the federal government.

There are two types of asylum. Migrants can present themselves at a border or port of entry and make an asylum claim; these are known as affirmative asylum claims and are adjudicated non-adversarially by asylum officers from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). Immigrants who are going through deportation proceedings in immigration court can also file an asylum claim; these are known as defensive asylum claims and they are adjudicated adversarially, with a lawyer from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) representing the federal government.

Migrants qualify for asylum under a specific set of conditions. The status is only granted to those who have suffered persecution or torture, or have “credible fear” that they will suffer persecution or torture, due to their “race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group.” These are clearly defined categories — with the exception of the last, “membership in a particular social group,” which has been defined differently over time depending on which presidential administration is drawing up the interpretive rules and guidelines. The Obama administration, for instance, included in this category those who were persecuted because of their sexual orientation; the Trump administration then removed that consideration from the category.

In 2002 the Bush administration began using a process called “expedited removal” to rapidly deport migrants apprehended at the southern U.S. border. To protect against the possibility of deporting individuals with legitimate asylum claims, migrants who express fear of being returned to their home countries meet with an asylum officer at a port of entry or in one of the 223 offices across the country, and that officer determines if a migrant’s claim has merit and should be considered in more detail. They do so by conducting what is commonly referred to as a credible fear interview.

In 2002 the Bush administration began using a process called “expedited removal” to rapidly deport migrants apprehended at the southern U.S. border. To protect against the possibility of deporting individuals with legitimate asylum claims, migrants who express fear of being returned to their home countries meet with an asylum officer at a port of entry or in one of the 223 offices across the country, and that officer determines if a migrant’s claim has merit and should be considered in more detail. They do so by conducting what is commonly referred to as a credible fear interview.

One of the most common misconceptions about the asylum process is related to this initial interview. Federal guidelines for this part of the process, established by Congress in 1996, mandate four questions, two of which are:

–Do you have any fear or concern about being returned to your home country or being removed from the United States?

–Would you be harmed if you are returned to your home country or country of last residence?

If a migrant answers “yes” to either of these questions they are found to have a credible fear. The migrant’s claim can then proceed forward, and because of the “expedited removal” approach established by the George W. Bush administration, it often does so as a defensive asylum case in immigration court.

But many misunderstand — or misrepresent — the initial interview as determinative for permanent entry into the country. It is not.

When an asylum officer determines that a migrant has a credible fear, that officer is not granting legal residency but simply granting access to asylum adjudication, most often through immigration court. The bar for gaining legal residency in the U.S. through asylum is dramatically higher — and far more capricious, particularly in the adversarial conditions of immigration court. Approximately 71 percent of asylum claims were denied in 2020. (That percentage dipped to 63 percent in 2021 but included far fewer new cases as most migrants seeking to make claims were prevented from doing so by Title 42, which, in many instances, barred entry into the U.S. as a public health measure related to the COVID-19 pandemic.) And for those coming from countries with some of the highest rates of violent crimes, the denial rates can be even higher. From 2001 to 2021, the denial rate for migrants coming from Mexico and Haiti, for instance, was 85 percent and 82 percent, respectively. The adverse circumstances that people are fleeing in these unstable places often do not fit within the predetermined asylum categories and the reasons for a denial are often based on very technical aspects of a case.

When an asylum officer determines that a migrant has a credible fear, that officer is not granting legal residency but simply granting access to asylum adjudication, most often through immigration court. The bar for gaining legal residency in the U.S. through asylum is dramatically higher — and far more capricious, particularly in the adversarial conditions of immigration court. Approximately 71 percent of asylum claims were denied in 2020. (That percentage dipped to 63 percent in 2021 but included far fewer new cases as most migrants seeking to make claims were prevented from doing so by Title 42, which, in many instances, barred entry into the U.S. as a public health measure related to the COVID-19 pandemic.) And for those coming from countries with some of the highest rates of violent crimes, the denial rates can be even higher. From 2001 to 2021, the denial rate for migrants coming from Mexico and Haiti, for instance, was 85 percent and 82 percent, respectively. The adverse circumstances that people are fleeing in these unstable places often do not fit within the predetermined asylum categories and the reasons for a denial are often based on very technical aspects of a case.

“Asylum law is very limited,” says Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, Policy Director at the American Immigration Council. “There’s a lot of circumstances where a judge can say, ‘I agree that you’ll be killed if you get sent back to your home country, but you’re just going to be killed for the wrong reasons. So you don’t qualify. Asylum law is harsh. It is not responsive to many of the concerns that cause people to migrate today.”

This Kafkaesque outcome is, unfortunately, a potential reality with asylum defined so narrowly — and often on technicalities — within the five categories of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, and social groups. If a family is fleeing Ukraine, for example, and winds up at a U.S. port of entry, they might not qualify for asylum. “Generally speaking,” says Reichlin-Melnick, “armed conflicts don’t provide the grounds for being granted asylum. If you’re a Ukrainian, you can’t get asylum from Russia, because you’re not in Russia. You’re a Ukrainian, and the Ukrainian government is obviously not the one persecuting you. There’s no asylum category for ‘Vladimir Putin invaded and he wants to conquer territory.’”

While migrants in such circumstances might gain other forms of temporary relief or even refugee status — an entirely separate immigration category, which is determined before a migrant travels to a destination country — the dangers faced by the vast majority of those fleeing Ukraine do not, as Reichlin-Melnick points out, directly relate to the five asylum categories.

While migrants in such circumstances might gain other forms of temporary relief or even refugee status — an entirely separate immigration category, which is determined before a migrant travels to a destination country — the dangers faced by the vast majority of those fleeing Ukraine do not, as Reichlin-Melnick points out, directly relate to the five asylum categories.

Republicans often point out that many migrants apply for asylum when their case has no real prospect of acceptance. As Reichlin-Melnick’s example illustrates, this is true. Not only is there no asylum category for citizens of a country being invaded by another country, but there is also no asylum category for climate change or economic hardship, both of which can be life-threatening and often drive much of the migration from places like Mexico and Haiti.

Adjusting asylum categories to include more possibilities would require action on the part of Congress, which is unlikely given the current political environment. Alternatively, Congress could create new visa categories — unrelated to asylum — that could take some of the burden off of the asylum adjudication process. If migrants seeking jobs in the U.S. or relief from catastrophic flooding could apply for visas from their home country, it would help reduce the number of people creating untenable processing demands at U.S. borders.

However, it’s been 32 years since Congress did a major overhaul to the existing visa categories. That means the last time our legal immigration system was significantly updated, the Soviet Union still existed. Needless to say, in the ensuing years the geopolitical structure of the world has changed dramatically, and our outdated, outmoded legal immigration categories have a sizable impact on the asylum system. “People don’t have a legal path to do something which is otherwise normalized, and I would say that human mobility and migration have been normalized throughout history,” comments Kocher, explaining that migrants who lack a legal pathway for entry into the U.S. will tend to utilize the asylum system.

However, it’s been 32 years since Congress did a major overhaul to the existing visa categories. That means the last time our legal immigration system was significantly updated, the Soviet Union still existed. Needless to say, in the ensuing years the geopolitical structure of the world has changed dramatically, and our outdated, outmoded legal immigration categories have a sizable impact on the asylum system. “People don’t have a legal path to do something which is otherwise normalized, and I would say that human mobility and migration have been normalized throughout history,” comments Kocher, explaining that migrants who lack a legal pathway for entry into the U.S. will tend to utilize the asylum system.

Kocher, Reichlin-Melnick and other experts who spoke with Ideaspace all identified creating new pathways to legal status as one of the most effective ways to reduce the strain on the asylum system. Work visas for migrants fleeing economic hardship or climate disaster visas for those fleeing environmental devastation are just a couple of possibilities, they say.

“The best way to reduce the number of people coming to the border for asylum is to expand legal immigration,” agrees Reichlin-Melnick. “That’s another thing that Congress is almost certainly not going to do right now. So we sort of end up with this very complicated situation where we have a lot of good ideas about what we could do. What is obtainable is a different question.”

***

How Can the Executive Branch Reduce the Backlog?

In December of 2021, after Democrats failed to get sweeping immigration reform into a reconciliation bill, Pres. Joe Biden pivoted to executive action. In March of this year, the Biden administration issued the “Interim Final Rule,” or IFR, which will go into effect this summer and includes dozens of changes to the asylum system.

One consequential change in the IFR is the opportunity for migrants to have their asylum claims — not just their credible fear statements — heard and fully evaluated by an asylum officer instead of an immigration judge or a Department of Homeland Security official.

One consequential change in the IFR is the opportunity for migrants to have their asylum claims — not just their credible fear statements — heard and fully evaluated by an asylum officer instead of an immigration judge or a Department of Homeland Security official.

Under the previous guidelines that governed the expedited removal and credible fear process, even migrants with very strong credible fear interviews were automatically referred to immigration court. This contrasts with the affirmative asylum system’s typical process, through which asylum officers have always had the ability to fully evaluate and approve asylum claims, only sending denied cases to immigration court.

“Under this new rule, people with very clear and obvious asylum claims will be able to be fully granted asylum, able to live permanently in the United States with asylum, within a matter of a few months,” says Reichlin-Melnick, noting that the current average wait time is nearly four and a half years. “The system, as it is now, is extraordinarily inefficient. There are people who have slam-dunk cases who still have to wait five years, and there are people who have really terrible cases, who are almost guaranteed losers, who get to stay in the country for five years anyway, and then there’s essentially the middle, which is where most people lie.”

The opportunity to have a case decided more immediately by an asylum officer is meant to capture the migrants in the first category — the “slam-dunk” cases that fit so clearly within the legal definition of asylum. All other claims would not be rejected but moved along in the adjudication process — but with a significant catch: The day a claim is put forward by an asylum officer, the clock starts ticking on a deadline to close the case and a determinative court hearing is scheduled 90 days out.

While most agree that the system is wildly inefficient and should be sped up, many immigration advocates and lawyers worry that the 90-day timeframe is too short. It often takes a migrant weeks or months to find a lawyer who will represent them — some migrants never do — and even once counsel is obtained there is much work to be done.

“It takes a while to adequately prepare your client before you have your merits hearing,” says Amy Grenier, Policy and Practice Counsel at American Immigration Lawyers Association. Grenier referenced her own experience and committee work by other asylum immigration attorneys to quantify the time each case requires: “It’s 40 to 80 hours of work, and within that an estimated 35 hours of face-time. During that face-time, you’re navigating trauma, you’re navigating cultural barriers, you’re navigating language barriers. It’s not something that can be rushed.”

Not only is it hard to navigate emotionally but it can be difficult geographically, too. With so many asylum seekers spending some or all of their wait-time in detention, it can be challenging for lawyers to connect with migrants in person. There are limitations inherent to a detention environment — limited visiting hours and remote locations, for example. Lawyers are often driving for hours from one far-flung location to another, straining their budgets and capacity, which further limits how many clients they can represent.

The American Immigration Council put out a letter expressing “grave concern” about the 90-day timeline, and that concern has been widely echoed by immigration advocates.

The Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR), which is part of the Department of Justice, issued the IFR. In a written statement to Ideaspace, EOIR says, “Throughout the credible fear process, noncitizens have opportunities to seek legal assistance and present their claims for protection.” The statement also points out that the timeline is only a guideline and that asylum seekers can still request continuances if they are needed to ensure due process.

The statement also underscores that the main point of the timeline is about addressing the growing number of pending cases: “The new process is designed to grant qualified cases promptly…. EOIR has a large backlog of cases, and the overall process is about creating a system that identifies those deserving of relief up front and allows for a thorough review by an immigration judge of those claims not granted by an asylum officer.”

The statement also underscores that the main point of the timeline is about addressing the growing number of pending cases: “The new process is designed to grant qualified cases promptly…. EOIR has a large backlog of cases, and the overall process is about creating a system that identifies those deserving of relief up front and allows for a thorough review by an immigration judge of those claims not granted by an asylum officer.”

There are other aspects of the IFR beyond the 90-day time frame that seek to speed up the process and also make it less capricious. Grenier singles out the creation of opportunities for dependents in a family unit to have their claims determined on an individual basis. “That’s important because sometimes the principal is not eligible but their child might be — and that is an improvement,” she says.

There are also technical inclusions in the IFR that aren’t as prominent as the 90-day timeline but could still have a dramatic effect. One such inclusion is a new requirement for what’s known as a “status conference.” This is when the lawyers for the federal government and the lawyer for the asylum seeker meet and agree on what issues should be covered at trial. “That sort of thing, in most other court systems, is very common,” says Reichlin-Melnick. “It’s never been common in immigration court. You’re supposed to reach out to the opposing attorney ahead of a hearing, but ICE is usually so overwhelmed and overworked that they just ignore your emails.”

So many of the asylum cases in that large middle group, the cases that require a deeper look, are often decided on a narrow legal issue. “Or there’s one or two factual issues,” says Reichlin-Melnick. “Rather than having an hours-long trial where every single issue is aired, it would be really helpful if the government would get together with a lawyer for the immigrant and agree, ‘Hey, our only concerns are issues A, B, and C. We don’t need to spend all of our time focusing on all these other issues.’ That can save everybody a lot of time and preparation and resources — and let the court hear more cases in a day.”

One other reform that is already under way is the move toward electronic filings — a need made glaringly obvious by the pandemic, which spurred various U.S. legal systems to further utilize electronic filings and virtual hearings when possible, including in the U.S. immigration court system. But Austin Kocher likens the effort to the first problematic iteration of the federal health exchange website that launched as part of Obamacare. “It’s not so exciting,” he says. “But if you’re going to have an electronic system, you’ve got to have someone who’s committed to keeping the systems running so that people are able to do that work. You’ve got to do a complete and accurate job. Having spoken with people in the Department of Homeland Security and in ICE in particular, I know that they have a really good data team. I know they’re really committed right now. They certainly have said that they’re very committed, and if the federal agencies were committed to two things, 1.), responsible data management practices, and 2.), really going in and doing the work, then I think that we could see a massive improvement. It could allow efficiencies within the court. It could allow for more clarity for the public about really what’s going on. So it does give me some hope. But the technology solution is only part of it. It’s not magic.”

One other reform that is already under way is the move toward electronic filings — a need made glaringly obvious by the pandemic, which spurred various U.S. legal systems to further utilize electronic filings and virtual hearings when possible, including in the U.S. immigration court system. But Austin Kocher likens the effort to the first problematic iteration of the federal health exchange website that launched as part of Obamacare. “It’s not so exciting,” he says. “But if you’re going to have an electronic system, you’ve got to have someone who’s committed to keeping the systems running so that people are able to do that work. You’ve got to do a complete and accurate job. Having spoken with people in the Department of Homeland Security and in ICE in particular, I know that they have a really good data team. I know they’re really committed right now. They certainly have said that they’re very committed, and if the federal agencies were committed to two things, 1.), responsible data management practices, and 2.), really going in and doing the work, then I think that we could see a massive improvement. It could allow efficiencies within the court. It could allow for more clarity for the public about really what’s going on. So it does give me some hope. But the technology solution is only part of it. It’s not magic.”

***

How Can Congress Help Reduce the Backlog?

Not all the reform action is happening within the executive branch. In addition to the IFR, there are currently two bills in Congress with bipartisan potential that aim to make the asylum adjudication process more efficient.

In April of 2021, Republican Sens. John Cornyn and Thom Tillis, along with Democratic Sens. Kyrsten Sinema and Maggie Hassan, introduced the Bipartisan Border Solutions Act. There is some overlap between provisions included in their bill and what the IFR is set to accomplish — most notably, more robust processing capabilities near ports of entry and a predetermined, expedited timeline for proceedings.

The bill also includes funding to hire more staff to expedite the asylum adjudication process and a more expansive program for allowing immigration advocacy organizations to communicate rights and procedures to asylum seekers so that each one can make a more informed decision regarding whether or not to move forward with a claim.

Perhaps most notably, the Bipartisan Border Solutions Act would empower the U.S. attorney general to define and prioritize “irregular migration surge events,” so that if a particular episode of violence or instability develops in a region of the world, the U.S. government would be better positioned to respond effectively.

The other bill with bipartisan promise that would improve the asylum adjudication process is the Real Courts, Rule of Law Act. Its primary function is to make immigration courts independent of the Justice Department, which would safeguard the court from shifting politics and priorities between presidential administrations.

The bill was introduced in February by Democratic Rep. Zoe Lofgren and received a committee mark-up in May, though it has not yet attracted any Republican co-sponsors. However, by framing the proposed legislation as a court system and “rule of law” bill, Logfren is hopeful she’ll gain support from some Republicans, according to a Democratic staffer who worked on the bill and requested anonymity due to the sensitive, ongoing task of attracting more co-sponsors.

“We settled on an Article 1 immigration court model,” says the staffer. “It is modeled after the tax court. It’s a way to pull the immigration court out from under the Executive Branch, professionalize it and have real standards of evidence.”

With the current system, migrants do not have guaranteed access to counsel, and cases are decided by DOJ attorneys, who act as de facto judges, all of whom have their own, idiosyncratic approach to the job. One such judge in Alabama, for example, denied 200 asylum claims in a row over the course of eight years, often on legal technicalities even when it was acknowledged by the judge that the migrant’s life was in danger if they returned home; while another judge in New York denied just 5 percent of asylum claims over a five-year span.

With the current system, migrants do not have guaranteed access to counsel, and cases are decided by DOJ attorneys, who act as de facto judges, all of whom have their own, idiosyncratic approach to the job. One such judge in Alabama, for example, denied 200 asylum claims in a row over the course of eight years, often on legal technicalities even when it was acknowledged by the judge that the migrant’s life was in danger if they returned home; while another judge in New York denied just 5 percent of asylum claims over a five-year span.

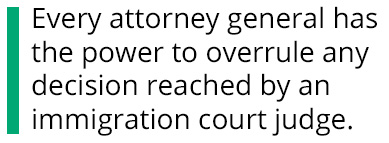

What’s more, each U.S. attorney general, appointed by the president, applies different rules and guidelines to the system. As attorney general, Jeff Sessions stated that 80 percent of those making asylum claims do not qualify for it and informed immigration judges that their performance review would be based on whether or not they processed a minimum of 700 cases per year and have fewer than 15 percent be overturned on appeal. In contrast, under Merrick Garland, the Justice Department re-authorized certain powers for immigration judges that had been stripped away by the Trump administration, restoring some of their judicial independence. But perhaps most notably, every attorney general has the power to overrule any decision reached by an immigration court judge.

“Lofgren really does see [the Real Courts, Rule of Law Act] as a good government-type bill that is addressing a long-term need,” says the Democratic staffer. “There really is not a lot of immigration policy per se in this bill. That’s why I think she hopes that it can get some broad support. We hear a lot of talk from both sides of the aisle about enforcing the laws on the books and the rule of law, and all of those types of things. Well, this is a way to make sure to help with that. To help ensure that the laws are faithfully executed. We think it’ll kind of create more confidence and integrity in the system overall.”

Beyond making the immigration court independent of the Executive Branch, Kocher and others question whether the asylum adjudication process belongs within the immigration court system at all. Kocher points out that U.S. law does not require this approach; it’s a policy decision made three decades ago. “[Adversarial adjudication has] been normalized in the United States,” he says, “but it’s actually quite peculiar. It’s not really in line with international law to have an asylum seeker who’s coming and requesting asylum go into a court setting where it’s an adversarial hearing, where you’ve actually got someone arguing against you. It’s absurd.”

Beyond making the immigration court independent of the Executive Branch, Kocher and others question whether the asylum adjudication process belongs within the immigration court system at all. Kocher points out that U.S. law does not require this approach; it’s a policy decision made three decades ago. “[Adversarial adjudication has] been normalized in the United States,” he says, “but it’s actually quite peculiar. It’s not really in line with international law to have an asylum seeker who’s coming and requesting asylum go into a court setting where it’s an adversarial hearing, where you’ve actually got someone arguing against you. It’s absurd.”

There are examples in other countries such as Sweden, Canada, and New Zealand where seeking asylum does not routinely put a migrant in an adversarial relationship with the government but allows for the claim to be processed as a diplomatic, inquisitive interaction.

***

Even before such a fundamental question regarding the adversarial nature of asylum adjudication is addressed, improvements to the electronic filing system, along with changes spurred by the IFR — albeit with caution regarding the 90-day time frame — could provide meaningful relief for immigration courts and asylum adjudication. Add to that the potential passage of the Real Courts, Rule of Law Act and the whole system starts to look meaningfully reformed.

Perhaps what’s most appealing about all of these possibilities is that, by and large, they stay away from some of the most fiery political discourse that’s often swirling around access to asylum. Those who wish to further restrict entrance into the U.S. for all migrants will continue to push back on these pragmatic solutions. But for members of Congress on both sides of the aisle who seek to make the system more effective and efficient, and thereby relieve episodic chaos at the border, each of these focused reforms holds very real promise.

Read More:

Capitol Hill Briefing No. 4

Strategic Inquiry No. 2