For Ideaspace’s first Strategic Inquiry, we examined the last time Congress passed major immigration reform, as well as failed attempts to do so in 2007 and 2013. Our aim was to explore how the next presidential administration and Congress might learn from these past efforts and succeed in passing new immigration legislation in 2021.

For Ideaspace’s first Strategic Inquiry, we examined the last time Congress passed major immigration reform, as well as failed attempts to do so in 2007 and 2013. Our aim was to explore how the next presidential administration and Congress might learn from these past efforts and succeed in passing new immigration legislation in 2021.

Among the people we interviewed was Mark Krikorian, the executive director of the Center for Immigration Studies. The Center espouses a nonpartisan position but generally supports immigration reduction and is widely viewed as conservative. While Krikorian’s thinking was addressed in our article, we wanted to share the entirety of our interview here, as we believe it presents a well-organized and insightful compendium of conservative theory on immigration policy.

Ideaspace: The last time that Congress took up immigration reform was the failed 2013 attempt. Why were you against it?

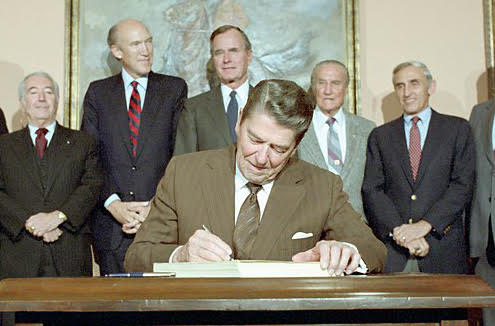

Mark Krikorian: That was the Gang of 8 bill, which had two basic problems. One is the same problem that the 1986 IRCA bill had, which is that amnesty would precede enforcement measures. And that’s the shadow that has loomed over all the immigration policy-making that has come since: the betrayal of the 1986 bill’s promise, which was amnesty first, for people who were established here, in exchange for a promise to enforce the immigration laws in the future, so we wouldn’t have this problem again. That was a lie, and I don’t mean it didn’t work out; I mean that people promoting the amnesty side knew they were lying. In 1990, just four years after the bill, once everybody had gotten the amnesty, they attempted to roll back the enforcement promises they made, they wanted to repeal employer sanctions and make it legal again to hire illegal immigrants. The only reason they were stopped is Corretta Scott King organized a number of Black leaders, had an open letter in The Washington Post, and killed that dead.

I: That was under the premise of protecting jobs for African-Americans?

MK: Yes. This was Ted Kennedy and Orin Hatch, along with the National Council for La Raza — they got together to try to essentially undo the bargain of 1986, once they got their half of the bargain. They knew they were going to do that. It was a con from the beginning.

My point is that the mistrust that generated — they also made sure there was no enforcement of the ban on hiring illegal immigrants — makes it virtually impossible to pass immigration legislation of this kind of package deal because everybody knows they’re lying. That was the problem in the mid-2000s when George W. Bush tried.

My point is that the mistrust that generated — they also made sure there was no enforcement of the ban on hiring illegal immigrants — makes it virtually impossible to pass immigration legislation of this kind of package deal because everybody knows they’re lying. That was the problem in the mid-2000s when George W. Bush tried.

I: It’s the nature of these two ideas. Amnesty, once you grant it, you can’t take it back. Enforcement ebbs and flows on all manner of things, like whether or not you fund it, and by how much you fund it.

MK: There is some of that. But a way to try to overcome that is to institute enforcement systems ahead of time, as a prelude to discussing amnesty. In other words, make E-Verify mandatory for all new hires, first. On its own, either with no deal, or maybe with something like DACA, which is a small piece of an amnesty. And once that’s up and running, then you come back and talk about amnesty.

Now the amnesty people, they’re projecting. They’ll say, “Yeah, but if you get that, then you’ll never come back to the amnesty.” It’s like, “Oh, you mean that we’ll try to screw you the way that you screwed us?” There is that problem, that they have no intention of holding up their end of any deal, so they assume that the other side has no intention of holding up their end of the deal. But the fact is that if mandatory E-Verify were in place — and I’d be happy to limit to only new hires first (in other words, not people who are already employed, it would still be an inconvenience for illegal aliens, but we wouldn’t be throwing all illegal aliens out of work overnight) -— then the illegal immigrants are still here. In other words, the political imperative to try and do something about it, to try an amnesty, doesn’t go away. In addition to E-Verify, I would actually want a functioning entry-exit system, too, to make sure we can identify and deal with overstays.

Now the amnesty people, they’re projecting. They’ll say, “Yeah, but if you get that, then you’ll never come back to the amnesty.” It’s like, “Oh, you mean that we’ll try to screw you the way that you screwed us?” There is that problem, that they have no intention of holding up their end of any deal, so they assume that the other side has no intention of holding up their end of the deal. But the fact is that if mandatory E-Verify were in place — and I’d be happy to limit to only new hires first (in other words, not people who are already employed, it would still be an inconvenience for illegal aliens, but we wouldn’t be throwing all illegal aliens out of work overnight) -— then the illegal immigrants are still here. In other words, the political imperative to try and do something about it, to try an amnesty, doesn’t go away. In addition to E-Verify, I would actually want a functioning entry-exit system, too, to make sure we can identify and deal with overstays.

I: So you believe a so-called grand bargain is impossible. You believe enforcement in exchange for amnesty is impossible to do in one fell swoop.

MK: Yes. Or, if you’re going to do them, you have to take small steps.

I: Can you do it with triggers?

MK: Any legislation like this creates a provisional status up front. Everybody gets amnesty up front. I mean, DACA people have been amnesty’d. They already have work permits, Social Security numbers, and driver’s licenses. The work permit is the amnesty. The only question about triggers is, Can you upgrade? And that’s not good enough.

The grand bargain idea does fail.

There’s two alternatives. One is smaller bargains, where if one or the other side welches on the deal, the counterpart side hasn’t given the farm away. So DACA amnesty in exchange for mandatory E-Verify but only for new hires. Maybe even only for new hires for companies with over 50 employees. A piece of amnesty in exchange for a piece of enforcement. Neither side gives everything away. Even if it’s DACA and DACA-eligible and TPS, that’s still 2 million people, not 11 million people. A chunk of amnesty in exchange for a chunk of enforcement, rather than trying to do everything in one grand gesture, which is just not good government, which is not good legislating.

The way I’ve always envisioned this happening is the enforcement comes first, maybe with some smaller amnesty concessions, but mandatory E-Verify is up and running, and a functioning entry-exit system is up and running (visitors come in and we track them — almost half the illegal population are visa overstays). Enforcement systems need to be up and running — yes, future Democratic congresses can gut them — but the systems need to be up and running.

Once that happens then I do see a grand bargain possibility. But it’s a different grand bargain than discussed. It’s almost the opposite of the Gang of 8 deal. It’s a quick, relatively simple amnesty for illegal immigrants who are here. I’m not interested in 13 years of jumping through hoops — that’s all bullshit. Rip the band-aid off, in exchange for — and here’s where the bargain is — deep permanent cuts in legal immigration. And I’m not just making that up. The No. 2 guy at La Raza years ago, Charles Kamasaki, he even suggested that as a possibility, of conceding lower future levels of immigration in exchange for legalizing people who are already here.

Because ultimately, if people are chiefly concerned with stabilizing and normalizing the status of people who are already here, then why would they insist on increasing immigration, if they could get that stability for the people who are their ostensible constituents, in exchange for not letting future people in who aren’t even here yet?

That was my other problem with the Gang of 8 bill, that it doubled legal immigration. And ultimately the problem is not that illegals are illegal, but the problem is that we have too much immigration — illegal or legal. So most of the restrictionists I know who do this for a living — as opposed to just random people on Twitter — would be happy to exchange amnesty for cuts in legal immigration, because the issue is not screwing foreigners, the point is reducing future immigration to create more stability and allow the economic and social processes to work, that can knit us together, that can improve the working conditions and wages for less skilled people. That can allow assimilation to take place. Frankly, you need an amnesty for all that to work. It’s just that amnesty in exchange for more immigration, and an amnesty that’s not gonna stop more immigration, is not fixing anything.

That was my other problem with the Gang of 8 bill, that it doubled legal immigration. And ultimately the problem is not that illegals are illegal, but the problem is that we have too much immigration — illegal or legal. So most of the restrictionists I know who do this for a living — as opposed to just random people on Twitter — would be happy to exchange amnesty for cuts in legal immigration, because the issue is not screwing foreigners, the point is reducing future immigration to create more stability and allow the economic and social processes to work, that can knit us together, that can improve the working conditions and wages for less skilled people. That can allow assimilation to take place. Frankly, you need an amnesty for all that to work. It’s just that amnesty in exchange for more immigration, and an amnesty that’s not gonna stop more immigration, is not fixing anything.

I: Your stance against legal immigration is based on economics and culture?

MK: I’m not against it. I’m for less of it. We have outgrown as a society mass immigration. Mass immigration is in conflict with the goals and characteristics of a modern society and that means all of the above that you were listing. With immigration skeptics, one guy will complain about the effects on the working poor; someone else will be concerned about assimilation; and a third person will be worried about security. They’re all the same thing. It’s just the blind man feeling different parts of the elephant and thinking he’s holding different things. It’s all the same elephant. And the elephant is that mass immigration is incompatible with the goals and characteristics of a modern society.

The point is that immigrants today aren’t really in any meaningful way different than immigrants of the past. What’s different is us. Modern society is different in kind than anything that’s ever existed before. And we simply can not deal with large inflows of less skilled or non sui generis workers. We don’t need that anymore. We’re a continental country, we’ve settled the continent. Higher levels of skills and education are necessary to succeed in the modern economy. A modern country always has some kind of welfare state. I’m a conservative, I want a more responsible, tighter welfare system that is less likely to result in dependency. But I’m not prepared to let poor people die on the steps of the emergency room or let kids starve to death. No modern society is going to tolerate that. And you can’t have a welfare state with a very high level of immigration and be able to afford it.

And then with assimilation. You know with a modern society there are two things that complicate assimilation that did not exist in the past. One is cheap, easy transportation and communications. One hundred years ago, you couldn’t just hop on a plane and go to your uncle’s wedding in Palermo and then just come back after a three-day weekend and go back to work. Now you can. You can live in two countries at the same time. And that’s a good thing. I’m all for it. Skype and airfare. But it complicates assimilation because it retards the process of a foreigner reorienting his psychological and emotional commitments from one place to another place.

And then the other aspect of modernity that has not existed before is that the elites in our society basically are opposed to assimilation. To put it very bluntly, our elites are anti-American. At the very least, they are post-American. Where do immigrants get their cues about how they’re supposed to behave? They get them from school. They get them from employers. They get them from Hollywood. They get them from sports. All of those institutions are at best ambivalent about America, if not actually hostile to America, like The New York Times. So the immigrants are not the problem. They’re prepared to be expected to stand up for the national anthem and all the rest of that. Most people are like, “I’m here, OK, what do you need from me?” Like my mom. She was the daughter of immigrants. She went to public school in the 1930s and ’40s, outside Boston. Her parents took her to school and the implicit bargain was, “OK, here’s our daughter, we’re taking her to church and teaching her how to be a young woman, you guys have to teach her about her new country. We have no idea, we just got here, that’s your job.” Today, some Guatemalan immigrant family bringing their kid to LA-unified school district is making the same implicit deal. “We’re working two jobs, we’re dealing with our family stuff, you guys are the ones to teach her how to be an American.” What the hell are they teaching them now? It sure as hell isn’t that George Washington is the father of our country. And so that’s on us. It’s not the immigrant’s fault. No immigrant today is any more or less interested in Americanism. Frankly, no immigrant today is any more or less interested in using welfare. All of this is on us — the good and the bad. And the fact is we’ve outgrown this.

Today, we have to be much more selective on the type of immigrant we take in, and on the amount of immigrants we take in. Not because immigrants are bad, and not because we’re bad. Conditions have changed.

I: When you talk about how modern society can not accommodate mass immigration, does automation play a role?

MK: Yes. It’s part of it. Economically there’s no question we don’t have the same need for as much less-skilled labor. But that kind of thing has been going on for a long time. It’s just now reaching its almost apotheosis. You just don’t need the same number of people who basically contribute a strong back and that’s about it.

I: With your idea of a “grand bargain,” how long would it take to legalize the 11 million undocumented people who are here today?

MK: I don’t have a magic number, but if you have the preconditions of the enforcement mechanisms…. With IRCA it was three or four years. The reason for that is I think IRCA did have a sensible thing in there where candidates for legalization got their provisional legalization right away but in order to get a green card they had to take a class on civics and history. A class for naturalization even though they weren’t naturalizing yet. A kind of basic intro to America, English, American history, the Constitution…. Doing all of that would take a little while, so I’d say three, four years, maybe five. I would want there to be some careful vetting, because with 11 million people some of them really are bad hombres, and you want to weed those people out. This idea that there should be some 13-year process of jumping through hoops, that’s just song and dance to calm the rubes and make the amnesty go down easier. I think it should be relatively simple, relatively few eligibility requirements.

I: Is what you’re describing politically possible?

MK: I don’t know. Not this year.

I: What conditions in 2021 would present the highest likelihood for a bill like the one you’re describing?

MK: It’s not gonna happen in 2021. But first of all, Trump needs to be reelected. I acknowledge that he’s a horse’s ass, but I’m gonna vote for him anyway, and happily. But it’s more than just Trump being reelected. It’s that the radical faction that has essentially taken over the Democratic Party, with regards to immigration, has to be defeated. I don’t mean it’s gonna go away, but it has to be politically marginalized. Because the Democrats really have become radicalized on immigration. There used to be some people who for labor, or social democratic concerns, or environmental concerns….

I: Just to be clear, let’s spell out those radical immigration positions.

MK: Sure. They’re opposed to applying immigration law to anyone who makes it past the border. And if there’s no consequences for violating immigration law then more people are going to come. You’re sending a message out, like we saw with the asylum loopholes at the border. People took us up on the fact that we were apprehending people, giving them a piece of paper, and then just letting them go into the United States, and more people did it, and it just kept going until we cracked down at least provisionally and stopped it. If Biden gets elected, that’s gonna start all over again.

In a sense, if I had to look forward into the future, maybe the way that we’re gonna get where I want to go is that Biden does win, and he and the Democratic congress de facto throw open the border. But maybe they can’t get an amnesty through because they don’t repeal the filibuster in the Senate. And things start spinning out of control, and then a Republican politician who isn’t a guy like Trump, someone who is able to talk to people who disagree with him without insulting them, comes in and cleans up the mess.

I don’t know, I’m not real hopeful anything is going to happen soon. On the other hand, next year what could conceivably happen is smaller nibbles in the right direction: Legalizing just the people who have DACA. If it were Trump, I could see a piecemeal bill in exchange for some meaningful enforcement measure, but maybe even small reductions in immigration. In other words, mandatory E-Verify for companies with more than 50 employees, or more than 100 employees, and getting rid of the visa lottery, in exchange for amnesty’ing DACA or even DACA-plus (DACA-plus meaning the DACA plus the DACA-eligible: 1.5 million or more). That’s not complete fantasy.

I: What efforts did you and your organization undertake to defeat the 2013 bill?

MK: That’s Roy Beck and NumbersUSA. We don’t lobby. What we did is just analyze the bill. That’s our lane. I’m pretty sure congress people — like Sessions — used our research. Numbers cited our stuff.

I: How much of a factor was Dave Brat successfully primarying Eric Cantor in the failure of the 2013 bill?

MK: That was very important. Now, would it have gone down without his defeat of Cantor? I don’t know. But the key thing is that the situation at the border was spinning out of control at the same time as Brat’s defeat of Cantor. In other words, what was happening at the border was increasing numbers of unaccompanied minors and families. That was picking up in 2012 after Obama’s DACA. And 2013 it was starting to get bad. And then Brat’s upset was almost like the straw that broke the camel’s back.

On its own, maybe it wouldn’t have done it, but it was the final straw that basically killed the chances of the bill in the House. There was no way Boehner was going to bring it up in the House after that. Even if Boehner brought it up before Brat, I don’t know that it would have passed. The Democrats, Rep. Luis Guitierrez, was saying Republicans told him they’d vote for it. But telling someone at the House gym they support the bill is one thing; actually putting your little voting card in the machine and pushing yes on the button, that’s a very different thing.

I: If you consider Brat as the canary in the coalmine for Trump and his rise to power on a platform of very hawkish immigration policies, then if Trump is soundly defeated in November, do you foresee a backlash against Trump’s more hawkish immigration policies and a potential return to those pre-Brat conditions on the Hill where compromise on immigration was in reach?

MK: In other words, would his defeat represent a repudiation of Trump’s hawkish immigration policies? The answer is no. The election is partly a referendum on Trump, as Trump. First of all, he’s not all that hawkish. He’s not a low-immigration guy. He’s really just a ramped up version of a regular Republican who believes illegal = bad, legal = good. In other words, he wants to compensate that he’s OK with high legal immigration by being very performatively tough on illegal immigration. He’s not that different from your regular swamp Republican. He’s just Trump. And he’s a horse’s ass. And he turns people off.

Trumpism, if you will, a kind of national populism — part of which is hawkish on immigration — isn’t going away. Even if he loses. But his loss will be on him. He hasn’t even maintained solidarity with his own supporters. If he loses, he loses because Joe Biden isn’t as loathsome as Hillary, and people have now had four years of Trump and the “Trump Show,” and the ratings are going down, and the voters might cancel the “Trump Show.” In a sense, his administration’s a TV show. So when “Firefly” was cancelled, it didn’t mean sci-fi was no longer popular. But four years from now, someone who’s not as obnoxious as Trump will be making the same points. Especially if the Democrats overreach.

Trumpism, if you will, a kind of national populism — part of which is hawkish on immigration — isn’t going away. Even if he loses. But his loss will be on him. He hasn’t even maintained solidarity with his own supporters. If he loses, he loses because Joe Biden isn’t as loathsome as Hillary, and people have now had four years of Trump and the “Trump Show,” and the ratings are going down, and the voters might cancel the “Trump Show.” In a sense, his administration’s a TV show. So when “Firefly” was cancelled, it didn’t mean sci-fi was no longer popular. But four years from now, someone who’s not as obnoxious as Trump will be making the same points. Especially if the Democrats overreach.

I: Would the way you operate change if Biden wins?

MK: Yes. In some ways it’s more fun because then you just get to attack the absurd over-reach that the Democrats will inevitably engage in.

I: Can you enumerate a couple of those bits of likely over-reach?

MK: They’re going to dramatically increase refugee resettlement. Way beyond anything we’ve had since Vietnam. That’s gonna blow up in their face. It will take a while. Biden is going to stop all deportations for the first 100 days of his administration. Which means there will be criminals who finish their term who are slated for deportation who they will have to release on the streets. Some of those people are going to go and kill people. All this stuff is going to blow up in their face. And apprehensions at the border will spike. What are they going to do with unaccompanied minors? Those numbers are going to go way up fast, right away, because more people will come because they know that they will be let go in the United States with a notice to appear. Even Obama, this whole kids in cages bullshit. The kids in cages storyline started under Obama because the Border Patrol was stuck with large numbers of minors that they had to process before they could hand them off to the next step and the pipeline got clogged, and they couldn’t have 17-year-old boys sleeping in the same room as 12-year-old girls. That’s what drove all of this. So they had to get chain link fences to create separate sections within these Border Patrol buildings which are not meant for detention at all. Either that or you’re going to have 17-year-old boys raping 12-year-old girls. Then what are you going to do? These problems don’t just go away because evil orange man is no longer in the White House. In fact, they’re going to get a lot worse, really fast.

Read More:

Strategic Inquiry No. 2