Donald Trump made the construction of a “big, beautiful wall” on the nation’s southern border a rallying cry of his 2016 presidential campaign. His evocation of what the barrier could accomplish as a protector of American values was vivid and effective. He rode into office on several waves, but one of the strongest he caught was a wave of immigration-related voter anxiety.

As the 2020 election approaches, many of the most intractable immigration-related challenges that colored the 2016 presidential campaign are still every bit as unsettled: the future of DACA remains uncertain, violence in Central America still drives asylum seekers to the southern border, construction continues of border barriers while its financing is deeply contentious, and there is no plan to address the long-term status of the undocumented population already in the country — 11 million people and counting. As this list of unsettled issues makes clear, immigration is a big policy umbrella.

The size of the umbrella is on display in a report by the Biden-Sanders immigration policy task force. The range of topics addressed there is vast, extending from family separations and border security to temporary worker visas and a backlog of more than 1 million immigration court cases.

While the nation struggles with a global pandemic and racial inequity, the stakes in the presidential race remain high in the immigration sector. The next administration will set our national compass and the contrast between the direction likely to be chosen by an elected President Joe Biden or a re-elected President Trump is dramatic.

While the nation struggles with a global pandemic and racial inequity, the stakes in the presidential race remain high in the immigration sector. The next administration will set our national compass and the contrast between the direction likely to be chosen by an elected President Joe Biden or a re-elected President Trump is dramatic.

If Trump wins re-election, he will presumably continue his first-term efforts to limit the scale of immigration with fewer temporary worker visas, a push for more aggressive deportation practices and increased border security, often established through executive orders since Congress has, for decades, been more graveyard than launching pad for immigration initiatives.

A Biden victory, particularly if accompanied by the Democrats capturing control of the Senate, could prove a watershed in the history of how the nation manages its borders and its undocumented population. The opportunity may open up for Congress to address long-festering problems and reshape immigration policy. The Democratic leadership has signaled that if Biden wins, action on immigration would be a top legislative priority, perhaps even the first major initiative. There is, however, a significant hazard that any such opportunity will be wasted if Biden and his allies do not succeed in building bipartisan support for a new approach to immigration.

It has been more than 30 years since the U.S. passed major immigration legislation. More recent efforts (in 2007 and again in 2013) have failed in high-profile ways. So what does the last successful legislative push and the subsequent failures teach us about what might be possible once the 2020 elections are settled?

***

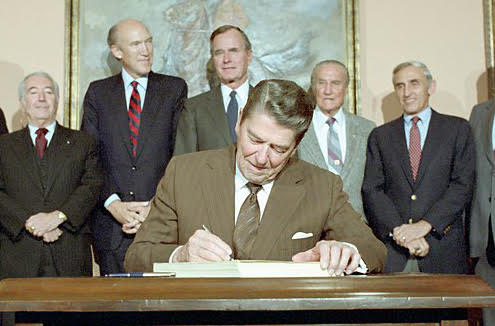

The current dynamics of our national conversation around immigration policy can be traced to 1986, the year Pres. Ronald Reagan signed into law the Immigration Reform and Control Act, or IRCA. That was the federal government’s last successful attempt to pass major immigration legislation. IRCA had three major features: it forbade an employer from knowingly hiring an undocumented worker, it gave legal status to the nearly 3 million immigrants who were in the country without documentation, and it strengthened border security. Reagan signed the bill in a ceremony next to the refurbished Statue of Liberty, saying, “The legalization provision in this act will go far to improve the lives of a class of individuals who now must hide in the shadows, without access to many of the benefits of a free and open society.”

IRCA originated as a bipartisan bill written by Republican Sen. Alan Simpson and Democratic Rep. Romano Mazzoli, and it was built on the idea that the amnesty would address the issue of the undocumented population already in the country while the workplace enforcement and increased border security would stop the flow of new arrivals. While the left was pushing for amnesty and the right was pushing for workplace law enforcement, both features were necessary to secure enough votes for passage and a presidential signature.

Charles Kamasaki, who is a senior cabinet advisor for UnidosUS — one of the country’s largest Hispanic civil rights organization — and was involved in the IRCA negotiations, puts it like this: “I don’t think it’s possible to call for generosity and compassion on the one hand without acknowledging the need to manage and control the border on the other.”

Charles Kamasaki, who is a senior cabinet advisor for UnidosUS — one of the country’s largest Hispanic civil rights organization — and was involved in the IRCA negotiations, puts it like this: “I don’t think it’s possible to call for generosity and compassion on the one hand without acknowledging the need to manage and control the border on the other.”

Kamasaki says he sees plenty of parallels between the tumultuous circumstances that led to the passage of IRCA and the current political climate. “No one would have guessed that any of these outcomes [embodied in IRCA] would have occurred at the beginning of the debate,” says Kamasaki. He points to three essential factors that made passage of the legislation possible.

The first factor was a willingness on the part of everyone to remain unpredictable. “The group actively defied conventional wisdom,” he says, “at every turn, in almost every way.” According to Kamasaki, every individual needs to be prepared and willing to step away from the orthodoxy of their political party. If individuals are not willing to do that, the intractable issues will remain intractable.

The second factor, notes Kamasaki, is that IRCA negotiators didn’t view the legislative process as linear. “I think it’s safe to say we approached our craft in much the same way that chaos theorists today approach any complex system like, say, the weather,” he says. Kamasaki points out that the IRCA negotiators collected massive amounts of data — including data from those on the opposing side — and used it to plan for various outcomes in the legislative process. “We tried to anticipate multiple scenarios … and tried to plant seeds of tactics that might work under each of those scenarios as the opportunities arose.”

The third takeaway from the 1986 negotiations was that, at pivotal moments, lawmakers on both sides of the aisle made what Kamasaki characterizes as “enormous concessions to their opposition.” He says that an unsung hero of the process was Esteban Torres, a Democratic congressman from California, who broke with the Hispanic caucus to lead a faction that worked very closely on a number of concessions sought by Republican leadership. And, of course, conservatives made the difficult call to agree to a process that opened a pathway to citizenship for large portions of the undocumented population.

But while IRCA might provide lessons about how to make new legislation possible, it also serves as a cautionary example. The idea, after all, was that the law would not only fix the status of those in the country without documentation but that it would cut off the influx of new undocumented immigrants. With more than 11 million undocumented individuals in the country today, it is clear that immigrants continued to enter the country unlawfully in large numbers after passage of IRCA.

But while IRCA might provide lessons about how to make new legislation possible, it also serves as a cautionary example. The idea, after all, was that the law would not only fix the status of those in the country without documentation but that it would cut off the influx of new undocumented immigrants. With more than 11 million undocumented individuals in the country today, it is clear that immigrants continued to enter the country unlawfully in large numbers after passage of IRCA.

“The shadow that looms over all immigration policy-making is the betrayal of the 1986 bill’s promise,” says Mark Krikorian, executive director of the Center for Immigration Studies, a conservative think tank that seeks to provide “reliable information” regarding the “consequences of legal and illegal immigration.” “People promoting the amnesty side, they knew they were lying. In 1990, just four years after the bill, once everybody had gotten the amnesty, they attempted to roll back the enforcement promises they made, and make it legal again to hire illegal immigrants.

“That betrayal makes it virtually impossible to pass immigration legislation of this kind of package deal [today] because everybody knows they’re lying,” says Krikorian, explaining that once amnesty is given you can not take it back, whereas future congresses can vote to defund or deprioritize enforcement and border security. “That was the problem in the mid 2000s when Bush tried.”

“That betrayal makes it virtually impossible to pass immigration legislation of this kind of package deal [today] because everybody knows they’re lying,” says Krikorian, explaining that once amnesty is given you can not take it back, whereas future congresses can vote to defund or deprioritize enforcement and border security. “That was the problem in the mid 2000s when Bush tried.”

Sen. Harry Reid introduced the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act in 2007 and there was bipartisan energy behind the effort — particularly from the White House, with Pres. George W. Bush prioritizing immigration reform as one of the last major policy goals of his administration. The bill incorporated provisions from earlier bills written by Republican senators Jon Kyle and John Cornyn, as well as Democratic Sen. Ted Kennedy. The 2007 bill had the same basic contours as IRCA: amnesty for the undocumented population in exchange for more enforcement and border security, but it also included a major overhaul of the worker visa program, significantly increasing the number of visas available to high-skilled workers.

For advocates like Krikorian, the bill held no guarantee that it would successfully cut off new illegal immigration. But the bigger deal-breaker was the generous new visa program. “Modern society is different from anything that’s ever existed before,” says Krikorian, citing automation and the rise of the information age. “And we simply cannot deal with large inflows of low-skilled workers. We don’t need that anymore.”

For advocates like Krikorian, the bill held no guarantee that it would successfully cut off new illegal immigration. But the bigger deal-breaker was the generous new visa program. “Modern society is different from anything that’s ever existed before,” says Krikorian, citing automation and the rise of the information age. “And we simply cannot deal with large inflows of low-skilled workers. We don’t need that anymore.”

Nevertheless, the bipartisan will to come together on immigration legislation endured into the Obama administration, and a new, serious push emerged in 2013. The effort was led by the so-called “Gang of 8,” four Republican senators and four Democratic senators who worked to negotiate the Border Security, Economic Opportunity and Immigration Modernization Act. This bill worked from the same basic principle of balancing increased border security and immigration enforcement with an overhaul of the visa system and amnesty for the undocumented population.

Former Democratic Rep. Joe Garcia, who, at the time, represented a district in south Florida that included much of Miami, was the sponsor of the House bill that mirrored the Senate bill. “The success of our immigration policy — long term — will depend on our trade policy,” says Garcia. He was hopeful that his Republican colleagues would support his bill because of the demands it fulfilled for the U.S. labor market. “Miami is an example,” he explains, “of a place where lax, liberal immigration policies turned what was, in essence, an agriculture and beach area into what can today arguably be called one of the great cities of the Americas. It is a trade hub, it has one of the largest international airports in the country, the largest cruise port in the world, and of course none of that would have happened if we had immigration policies that were more restrictive to all the talent that wants to come.”

Garcia was also hopeful that Republicans would be motivated by the growing numbers of Hispanic voters. “One of the great things that the Bushes understood,” he says, “was that first generation Hispanics tend to be very conservative. But after a while they started thinking I can’t vote for these guys because this party is going to attack my kids. So part of the problem for the Republican Party is that they started to embrace attacks on these communities and these attacks became racist. Hispanics can agree with all the Republican conservatism that they get spoon-fed at church, but in the end the attack on their children is unacceptable.”

Initially, Garcia’s 2013 effort held much bipartisan promise, as he secured three Republican representatives to be co-sponsors of his bill. But, as Garcia points out, “none of those people are in Congress anymore.”

The Senate passed its bill with a resounding vote of 68-32, but House Speaker John Boehner did not bring up Garcia’s bill in the House because of splintering on the far right driven by the intense data and advocacy work from immigration reductionists like Krikorian and NumbersUSA. Ultimately, the ghosts of IRCA remained.

Soon after the legislation failed, Rep. Eric Cantor, a key member of the Republican House leadership, lost his seat in a primary challenge from Dave Brat, who ran as an immigration hawk. As the Republican Party processed the shock of that electoral outcome, it became clear that bipartisan immigration legislation was not going to be possible in the near term.

Soon after the legislation failed, Rep. Eric Cantor, a key member of the Republican House leadership, lost his seat in a primary challenge from Dave Brat, who ran as an immigration hawk. As the Republican Party processed the shock of that electoral outcome, it became clear that bipartisan immigration legislation was not going to be possible in the near term.

“Part of the problem,” says Garcia, “is that you have a Republican Party that has changed its views on this. The rhetoric around immigration is horrific — it’s xenophobic, it’s mean and it has no basis in real policy. I think the Republican hatred for Obama extended to everyone who didn’t look, quote unquote, like a model American from two centuries ago.”

***

If Trump is re-elected, we can expect a continuation of the policies he has already put forward, largely carried out through executive action instead of legislation: reducing the annual number of temporary workers and asylum-seekers who are granted legal status in the country, increased deportation enforcement, and use of detention and family separations as deterrents.

On the other side of the ballot, the Biden-Sanders task force released a plan that focuses on rolling back Trump administration policies: cutting off use of emergency funds to build the southern border wall, ending the travel ban for visitors from predominantly Muslim countries, reunifying families that are separated at the border, protecting DACA enrollees, restarting aid to the troubled Northern Triangle countries of Central America, raising the number of people granted asylum back up to Obama administration levels, and considering factors such as domestic violence and abuse against the LGBTQ+ community when making a determination on asylum applications.

The task force has put forward new policy priorities, too: expanding the annual cap on temporary worker visas, increasing workforce protections, reducing use of detention for migrants, more oversight for ICE as well as Customs and Border Protection, considering climate change as a root cause of migration, and, of course, a path to citizenship for those who are already in the country without documentation.

Perhaps one of the most telling lines from the task force policy paper addresses the long-term structural challenges that the country faces: “The truth is that our immigration system was broken long before Pres. Trump came into office, and his departure alone won’t fix it.”

Perhaps one of the most telling lines from the task force policy paper addresses the long-term structural challenges that the country faces: “The truth is that our immigration system was broken long before Pres. Trump came into office, and his departure alone won’t fix it.”

Those who have been in the trenches of previous immigration reform efforts acknowledge how challenging the issue is, but there are surprising points of consensus that may provide a path forward.

There is, for instance, broad support across the political spectrum for increasing enforcement of labor laws, whether one’s priority is protecting American workers or making sure immigrants are not taken advantage of. “The powerful thing,” says Kamasaki, “is that arguing for vigorous enforcement of our labor laws is potentially unifying. Laws protecting workers aren’t very well enforced for anybody — immigrants or citizens. There’s an opportunity to use a labor law enforcement regime as a fulcrum for immigration reform. If it were well-funded and enforced it could raise standards for everybody. That should be something that is attractive to miners or janitors or service workers who aren’t immigrants.”

Border security is another area with a great deal of potential for consensus. Even if most of the country opposes the idea of a continuous wall on the southern border, leadership from both political parties generally supports using barriers and other tools as appropriate to interdict crime at the border and improve the channels that allow people and goods to enter the country legally. “People often conveniently forget,” says Kamasaki, “that Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, Joe Biden, and Bernie Sanders all voted for [portions of] the fence during the George W. Bush administration. A rational border enforcement policy will include some physical barriers. And the next generation of successful reformers are going to have to embrace the basic legitimacy of immigration enforcement writ large.”

Border security is another area with a great deal of potential for consensus. Even if most of the country opposes the idea of a continuous wall on the southern border, leadership from both political parties generally supports using barriers and other tools as appropriate to interdict crime at the border and improve the channels that allow people and goods to enter the country legally. “People often conveniently forget,” says Kamasaki, “that Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, Joe Biden, and Bernie Sanders all voted for [portions of] the fence during the George W. Bush administration. A rational border enforcement policy will include some physical barriers. And the next generation of successful reformers are going to have to embrace the basic legitimacy of immigration enforcement writ large.”

For Krikorian, it comes down to getting over the ghosts of legislation past and rolling out policies in a sequence that helps reestablish the trust that he feels was lost after the passage of IRCA when amnesty was broadly granted but the promised law enforcement and border security mechanisms were not effectively enforced.

“The way I’ve always envisioned this happening,” says Krikorian, “is the enforcement comes first — maybe with some smaller amnesty concessions, but mandatory E-Verify is up and running. … Enforcement systems need to be up and running — yes, future Democratic congresses can gut them — but the systems need to be up and running. Once that happens then I do see a grand bargain possibility. But it’s a different grand bargain than [has been] discussed. It’s almost the opposite of the Gang of 8 deal. It’s a quick, relatively simple amnesty for illegal immigrants who are here. … Rip the band-aid off in exchange for deep permanent cuts in legal immigration.

“Ultimately, if people are chiefly concerned with stabilizing and normalizing the status of people who are already here, then why would they insist on increasing immigration if they could get that stability for the people who are their ostensible constituents, in exchange for not letting future people in who aren’t even here yet?”

While the country is still deeply divided on this issue, Kamasaki reminds us that the divisions were there in 1986, too — and that change seemed every bit as impossible then. Just three weeks before the passage of IRCA, one leading lawmaker referred to the bill as a “corpse.” Another said he wanted to wash his hands of it. Still, it came together.

“I do think a different mindset among today’s reformers might be helpful,” says Kamasaki. “That mindset might include a willingness to dispense with conventional wisdom that pretty much says every big bill is dead upon arrival. Another big lesson is to talk to people on the other side of the issue. Communicate your message beyond your base. And if one wants results, one must be willing to break with partisan orthodoxy. It’s important not to be bound by the current political landscape. Don’t just envision a different future but several different futures.”

Read More:

Strategic Inquiry No. 2

1 comment on “In 2021 Can Congress Exorcise the Ghosts of a 1986 Bargain?”

While NumbersUSA certainly offered robust opposition to the Senate “Gang of 8” bill (and its House counterpart), I was intrigued by your timeline. It departed from the PBS documentary and ProPublica’s reporting that claimed that Cantor’s loss was what buried the legislation’s chances. Although neither you nor PBS mentioned it, I’d submit for consideration that the reason that a “comprehensive” immigration bill “was not going to be possible” for the rest of the Obama presidency was his move to enact DAPA.

Comments are closed.