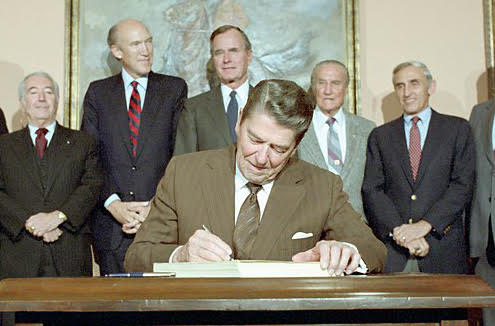

Earlier in the year, Ideaspace talked to Charles Kamasaki about a range of immigration issues. For decades now, Kamasaki has been on the front lines of policy reform. As a longtime senior member of the National Council of La Raza, one of the nation’s largest Latino advocacy organizations, he was directly involved in negotiations for the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, or IRCA, and to a lesser degree the Immigration Act of 1990 — the last major comprehensive immigration reforms passed by Congress, nearly two generations ago. Kamasaki, who is still a senior cabinet advisor for UnidosUS (the name which the National Council of La Raza adopted in 2017), recently chronicled the passage of IRCA in his book Immigration Reform: The Corpse That Will Not Die. For more information on the book, visit www.charleskamasaki.com.

Earlier in the year, Ideaspace talked to Charles Kamasaki about a range of immigration issues. For decades now, Kamasaki has been on the front lines of policy reform. As a longtime senior member of the National Council of La Raza, one of the nation’s largest Latino advocacy organizations, he was directly involved in negotiations for the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, or IRCA, and to a lesser degree the Immigration Act of 1990 — the last major comprehensive immigration reforms passed by Congress, nearly two generations ago. Kamasaki, who is still a senior cabinet advisor for UnidosUS (the name which the National Council of La Raza adopted in 2017), recently chronicled the passage of IRCA in his book Immigration Reform: The Corpse That Will Not Die. For more information on the book, visit www.charleskamasaki.com.

We asked Kamasaki about his experiences at the negotiating table for the 1986 and ’90 reforms, his take on the current shape of immigration policy, and what he thinks might be possible in the Congress that will convene in 2021. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

***

Charles Kamasaki: The next generation of successful reformers are frankly going to have to embrace at least the basic legitimacy of border enforcement or immigration law enforcement writ large.

I think there are at least three reasons to do that.

Reason No. 1 is almost regardless of where one is on the spectrum of more or less immigration it seems to me you have to start with the basic principle that every sovereign nation gets to enforce its borders however it chooses. Regardless of where one would draw the line in terms of more or less immigration, I think you have to start with the principle that it’s the right of the American people, in this case, to draw a line somewhere. Where that line ought to be drawn is a matter of contested debate and should be. That’s reason number one.

Reason No. 2 is that I don’t believe there is a very strong case to be made for unfettered immigration or unlimited immigration or open borders or whatever term you want to apply. I don’t think you can make the case that that’s necessarily good for the [immigration] community that many of us claim to represent. … I’m not sure it’s an accident that this period of low upward mobility and stagnant wages is occurring at the same time as our highest levels of immigration over the last 100 years. I don’t think immigration is the major cause of that and I think a lot of social scientists and economists would agree with me on that. But, at the same time, I wouldn’t discount that it’s a factor. If you start with that notion, then it seems to me that some level of control is appropriate.

Finally, Reason No. 3 is that I don’t believe it’s politically possible — or, even if it were possible, I don’t believe it’s sustainable — to have an immigration policy that would legalize the status of the majority of undocumented people, which for me is our top, most urgent immigration reform priority, without also including some heightened immigration law enforcement. I just don’t believe that it’s possible to call for generosity and compassion on the one hand without also acknowledging the need to manage and control the border on the other.

Finally, Reason No. 3 is that I don’t believe it’s politically possible — or, even if it were possible, I don’t believe it’s sustainable — to have an immigration policy that would legalize the status of the majority of undocumented people, which for me is our top, most urgent immigration reform priority, without also including some heightened immigration law enforcement. I just don’t believe that it’s possible to call for generosity and compassion on the one hand without also acknowledging the need to manage and control the border on the other.

Ideaspace: A big part of your message is about expending effort on achievable solutions — solutions that are politically possible. You have said that there are prescriptions out there that you’re personally in favor of but that you don’t see as politically possible right now. Can you name one or two of those prescriptions?

CK: When I was writing my book, I toyed around with a strategy that Emily Ryo, who’s a professor at USC, has begun to develop. I just didn’t feel like I had the chops to develop it and I don’t think it’s realistic. It’s basically a race neutral immigration enforcement regime. Currently, almost all immigration enforcement rests on some form of racial profiling. The majority of immigrants, writ large, and of undocumented immigrants, are no longer coming from Mexico or Latin America, but from Asia, except for the recent Central American surge, which is a different dynamic. Yet, historically, and this still continues to be true, 95 percent or more of people who are deported are of Latin American origin. Well over 90 percent are from Mexico. You’ve got to ask the question, what is going on here? If half of the new arrivals who are undocumented are not Latino and yet pretty much all the deportations are Latino, what is going on?

Professor Ryo has also some really interesting studies based on deterrence theory. She’s looked at things, like, why do people abide by traffic laws or why do people abide by the tax laws? She generally finds, as most criminologists have found, that compliance tends to be high when there’s a high degree of confidence that the enforcement regime is fair. Everybody speeds a little bit, but there’s generally a high degree of compliance: people stop at traffic lights or stop signs even when nobody’s watching. She contrasted that with a series of surveys she did of undocumented immigrants in detention and in other settings. Many of them made the argument that they thought immigration enforcement was highly unfair and that they were being targeted because they were Latino, that lots of other people were getting away with this. They felt less of a moral compunction, as it were, to comply. Compliance with law enforcement, writ large, generally rises when there’s a fundamental agreement about its fairness. I think if there were a more race neutral immigration enforcement regime, I think there would be a lot higher voluntary compliance.

Now, that’s not a very popular view in some circles because frankly what that would require is a lot more enforcement against populations that largely go under the radar now. We have had large numbers of undocumented Irish, large numbers of undocumented East and South Asians. To some pro-immigrant advocates, they would say it would be unfair to target them. What I would say is think how unfair it feels to people who are targeted. That’s one of the proposals I would have.

A second proposal, which actually may be more realistic, would be to have a neutral expert body determine overall levels of immigration. I could see something like a Federal Reserve, if you will, consisting of experts. There would be some connection to the political process, but they would have terms that would be largely insulated from politics. I could see something where they might set ceilings of legal immigration for workers or family visas, or refugees that might rise or fall depending on circumstances abroad and here in the U.S.

Not that experts are ever going to be perfect but, if it were seen that immigration levels were being set fairly — based on expertise rather than the whims of politicians — I do think there would be more trust.

I: Regarding Professor Ryo’s race neutral immigration enforcement regime, does she put forth an idea of what that would practically look like?

CK: I’m not sure. It’s not impossible to imagine. I imagine it would be like what a lot of police departments these days that are under consent decrees for having racially profiled in the past have to comply with now.

For example, I think there are some Southern California jurisdictions that were sued by the ACLU for racial profiling. Certainly some in the deep South that were sued by the Justice Department for consciously racially profiling. The immigration context in Phoenix might be one of those as well, with Sheriff Joe Arpaio, where they have to report specifics on race and ethnicity on their stops, the reason for the stops, and the outcomes of the stops. Not that it probably is perfect, but it’s amazing how those numbers change over time once police officers and the police chief and the mayor know that those statistics are going to be published every year. They start to equalize pretty fast. That’s the kind of regime I would imagine. This may be a little bit more extreme, but it’s a fairly common principle in criminal law that you can’t use the forbidden fruit, as evidenced in a prosecution, as it were. One could also imagine being able to challenge an immigration enforcement action on the grounds of racial profiling. Therefore, ICE or CBP might be deterred from doing that if they knew that it would be subject to challenge.

I: Are there any ideas that have been put forth in the 2020 Democratic presidential primary that you think are both good and realistic?

CK: Yes. One piece of Bernie Sanders’s immigration plan stood out to me as being very different. To me, it’s also attractive because it’s potentially unifying. Part of his immigration plan proposes very rigorous labor law enforcement. Essentially he’s proposing to have immigration law enforcement take a backseat to labor law enforcement. The rationale is pretty clear. The reason employers hire exploitable, unauthorized immigrants is because they’re exploitable and you can violate labor laws and wage and hour laws with impunity. Well, it turns out, as Sanders points out, that those aren’t very well enforced for anybody in this country. He suggests as a fulcrum of his immigration plan a labor law enforcement regime that would be very rigorous, very well-funded, to try and raise labor standards for everybody. Then, the incentive to hire unauthorized immigrants is substantially reduced and moreover, as it turns out, wages and working conditions would rise for everyone. That should be something that should be attractive to the mine workers or janitors or other service workers who aren’t immigrants. To me, as a concept, that’s a very powerful one.

I: Yes. It’s not only practical, but it gets away from all of the inflammatory language. And it gets us away from the immigration language. We’re still talking about that, in effect, but we shift the framing to labor, which is something that applies to any working person or anyone who lives with a working person.

You have said that for you it’s really about controlling the flow. In practical terms, whether it’s two people coming to the country or 100,000, what does it look like to control the flow of immigration?

CK: In terms of what an enforcement regime or a control regime would look like to me, the first and most important principle, and I know politicians have trouble doing this, is you can’t oversell. When it comes down to issues like migration, unless we really want to live in a police state, then there’s going to be some messiness at the margins. That’s just a fact. Anyone who says they’re going to have perfect control of the border or perfect control of people who come and overstay their visas is just lying because that just isn’t going to happen. The second thing I would say, just as a caveat, is it’s by definition, impossible to account for the unforeseen.

To give you an example, 20 years ago the EU would’ve said to the United States, and they did say to the United States very often in these transatlantic conferences, “Oh, you guys. You’re still having all these troubles with immigration. We’ve got it under control. We know exactly what we’re doing. We have open immigration among the EU countries. We have no borders between any of the EU members. We have Turkey and Greece and Northern Africa entry points and those are very well policed and very well controlled. We know how to do this.” You fast forward 15 years and they have 2 million refugees from the Middle East. You just can’t account for the unforeseen. I dare say no one predicted that when George Bush sent troops into Iraq that that would result in a massive flow of refugees to Europe a decade later. No one would’ve predicted that.

With those two caveats, I would say the first thing that’s important is the number of legal immigrants and temporary workers that are allowed in the country should more or less approximate the economic demand for them. We know from history that every time our legal immigration quotas are lower than the demand for those workers that those workers are going to come anyway. I would think that’s an important principle. Now, how many of those should come on a temporary work visa or some sort of provisional visa where they can earn legal status over time, and how many of them should come in as family immigrants versus worker immigrants? I mean, all those are issues that need to be debated. I guess, the principle there is that the number of people allowed in should approximate the economic and social demand for them. I should throw in social considerations just because there are categories of family visas that are indirectly economic, but really just as much social. To give you an example, a lot of young people in this country who have parents abroad will tend to want to petition for them right around the time the kids start coming. Well, that’s not a surprise. Many of them would much rather have a parent in the country helping them care for their kids so they can go off to work, rather than having to pay the very high cost of childcare and trust people they don’t know with their kids. Well, that has an economic benefit, but it’s not necessarily a direct one. There’s also a social element to that as well. That’s the first principle.

The second is that any rational enforcement regime requires some border enforcement. People often conveniently forget that both Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, when they were in the Senate, and I would add Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders, all voted for the fence [Secure Fence Act of 2006].

That, to me, isn’t a gotcha thing, it’s that any rational immigration policy is going to have border enforcement and any rational border enforcement policy is going to include some physical barriers. That is, I think, kind of an essential element. I don’t think we’ve quite figured out totally how to manage visa overstays, but I think that’s an area that probably does require more enforcement. Let me give you the classic example of that. Are you familiar with the three- and 10-year bars?

I: Yes, I am.

CK: Okay. As you may know, the three- and 10-year bars do not apply to people who are visa overstayers. They only apply to people who are so-called EWIs, who enter without inspection. That has a couple of effects. One is it’s therefore not a big surprise that the proportion of the undocumented population that is growing is consistently visa overstayers, not people trying to come across the border. The second thing, though, is the reason it doesn’t grow massively is because a lot of those people adjust to legal status. They can adjust by marrying a U.S. citizen. They actually may have a lawful permanent resident visa pending, but their number hasn’t come up yet, so they might enter as a student or enter as a tourist or enter as a whatever and then overstay. Then their number comes up and they can just adjust to lawful permanent resident status. I think the three- and 10-year bars are crazy, but some kind of limitation on adjustment for entering illegally is not, to me, crazy. Geez, if you’re going to apply it to people who cross the border I don’t see what the moral or philosophical basis would be for not applying it to people who enter by coming by plane or coming in by boat.

Finally, I would say, in terms of interior enforcement, for all the reasons that we know, that it’s highly disruptive to people, it threatens violations of civil rights, it affects parents of U.S. citizens and others. I would have fairly minimal interior enforcement, except in the case of people who are true security risks. I think that would be more along the lines of detective work than raids.

That would be my three-legged stool, as it were. A rational legal immigration policy, a rational border enforcement or, to be more accurate, border and other ports of entry. And then finally, a highly selective, very targeted interior enforcement regime really trying to find people who truly are terrorists or security risks to others.

I: Do you see anything on your radar that we could do in terms of Central American policy? So much of the enforcement is around Central Americans and Mexicans. Are you aware of proposals that could help stabilize that part of the world?

CK: Yes, but here’s the problem. The Northern Triangle countries either are or are very close to being failed states. Maybe with the possible exception of El Salvador, which at least has a democratic government that’s relatively stable. And, given the influence of the cartels not just in those three countries, but in Mexico as well — if you talk to experts, what they’ll tell you off the record is while they support the concept of a Marshall Plan for Central America, the execution would be devilishly complicated. We would frankly have to be prepared to accept high degrees of fraud and high degrees of corruption.

I guess, what I would say, is it has taken a long time for those really truly horrible conditions that exist in some of those countries to get to the state that they’re in now and it’s going to take some time to reverse those. Other than that broad caveat, I guess what I would say is I do think there needs to be increased aid, but it can’t just be that. It needs to be accompanied by fair but firm refugee and asylum policies at the border. And, by some innovations that I think the Obama administration began playing around with in 2014, more in-country processing, so people don’t have to cross through Mexico to come here. More safe havens and safe zones in the region. The fact of the matter is, in almost any mass asylum or mass refugee situation, whether it’s the Middle East or sub-Saharan Africa, or right now in Venezuela, the vast majority of people who are displaced actually stay in the region.

I would see, in an ideal world, whether it’s the UN or the OAS or some other multilateral body, some institution helping to ensure that for people who have legitimate fear for their safety, but who may not qualify for refugee status or may not qualify for asylum, that there is at least safe haven for them in the region. I think that would maybe relieve some pressure in some of those areas while we test and implement a Central America Marshall Plan and responses to the cartels. People will say, “Gosh, that’s so ambiguous and vague and amorphous and it would take so long.” I acknowledge all those things, but I also look to places like Colombia where it was pretty close to a failed state 25 years ago. Through bipartisan support over time the influence of the cartels was substantially reduced. There is a pretty democratic government that’s been established. So I would say it’s possible.

NOTE: The opinions expressed by Charles Kamasaki are his own and may not reflect the views of UnidosUS or the Migration Policy Institute.

Read More: